THE LOST TESTAMENT

OF SAM BUTERA:

THE RISE & FALL

OF ‘THE WILDEST SHOW

IN VEGAS’

BURT KEARNS

February 16, 2021

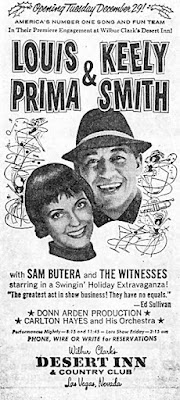

Sax player and arranger Sam Butera was ‘Keith Richards to Louis Prima’s Mick Jagger’ once he joined the great trumpeter, singer and bandleader in Las Vegas in 1954. With vocalist Keely Smith, the group leaped into national consciousness on the wings of songs like ‘Just A Gigolo,’ ‘Jump Jive An’ Wail’ and ‘That Old Black Magic.’ Burt Kearns and Rafael Abramovitz sat down with Butera in 1991 and got the real story about the Mob’s connection to Vegas and the raunchy private lives of the musicians. The interviews were never published. Some are now shared here, on PKM.

Sam Butera was a red-hot, 27-year-old rhythm and blues tenor saxophone player from New Orleans when, on Christmas Eve 1954, he got the call to work with his musical hero, Louis Prima, in Las Vegas. The result — a joyful mix of Dixieland jazz, jump blues and rock ’n’ roll, combined with the impeccable vocals of a deadpan female singer — launched “Louis Prima & Keely Smith with Sam Butera and the Witnesses” into the biggest musical success the gambling city had yet to see. Butera’s wailing, honking sax and innovative arrangements provided the crucial spark, and recordings of songs including Just A Gigolo, When You’re Smiling, Jump Jive An’ Wail, and That Old Black Magic extended their fame far beyond the Vegas Strip.

The New Orleans Times-Picayune referred to Sam Butera as “Keith Richards to Prima’s Mick Jagger.” Butera was also known for his fierce loyalty to Prima and as a man who knew how to keep secrets. Like the mobsters who ran the casinos and clubs where he worked, and the goodfellas who made up a significant portion of his fanbase, Butera lived by the code of omertà, and when he died in 2009, it was assumed he’d taken his secrets with him. No one knew that in February 1991, he told all. Over days in the living room of his home on Chapman Drive in Las Vegas, Butera revealed to journalists and screenwriters Burt Kearns and Rafael Abramovitz the story behind the rise and fall of “The Wildest Show in Vegas.”

The interviews were never published. What follows are highlights from the lost testament of Sam Butera.

(VIDEO: Louis Prima – Sam Butera plays Night Train -with Keely Smith, Sam Butera and the Witnesses.)

I worked for Louis Prima’s brother, Leon, for four years at the 500 Club on Bourbon Street [in New Orleans]. And I always loved Louis Prima. My mother and father used to tell me about him when I was a little boy growing up. Louis Prima used to play at the Saenger Theatre in New Orleans. That’s when they had vaudeville and stuff. And my mother and father loved the way he sang and loved the things that he did. They always talked about him.

I was always interested in meeting him one day, maybe getting a chance to work with him. ’Course, this was wishful thinking at that time. It was, I forget the year, it was 1954, I think it was. I wasn’t working with Leon at that time. I had formed my own group and I was doing the Sunday afternoon jam sessions at a place called Perez’s Oasis, which is on the Airline Highway, and I had a hell of a following. And Louis Prima was working there. This is when Louis and Keely were… “on their last leg,” you might say. They were there with a twelve-piece band, playing stock band arrangements, and things were not going well for Louis or Keely.

And so, Mr. Perez told Louis, he said, “I got this kid.” I was twenty-seven. He says, “I’ve got this young man who plays the Sunday afternoon jam session. Would you mind if he did it with you? ’Cause he has a wonderful following here.” And Louis said, “Of course not. It would be a pleasure.” So I went out there, and then I got an arrangement, walked on stage, told the guys the key and just played with the rhythm section. Never sang. Just did all instrumentals. And Louis and Keely were very impressed with my performance, the way I handled myself and such onstage. And after we got through, Louis called me on the side and said, “Well, we’ll be leaving here. I don’t know where we’re headed for, but –” he said, “if ever something happens, I’d love to have you with me,” and so on. I didn’t– you know, you hear one thing, in one ear and out the other. I said, “Well, whatever.” You know, fine.

Lounge performers were on a lower rung

of the show business hierarchy. All that

was about to change when Sam Butera

pulled into Las Vegas on December 26, 1954.

So I was doing a couple of nights at the Monteleone Hotel [in the French Quarter], with a band. I worked there because I had gotten hurt in an automobile accident so I couldn’t go on the road. I just had to get something where I sit down and be comfortable. So I was working at the Monteleone Hotel, all of a sudden I get a call. It’s from Louis Prima. He said, “Sam, it’s happening!” I said, “What?” And he said, “Las Vegas is happening for us!” I said, “Boy, that’s great, Louis.” He said, “When can you come up?” I said, “Well, I don’t know,” I said. “When would you want me?” He said, “Come tomorrow!” I said, “Tomorrow’s Christmas!” He said, “What’s the matter? What difference it make?” I said, “No, I got to spend Christmas home.” I said, “I’ll be up on the twenty-sixth.” He said, “Well, bring a drummer and a piano player with you.”

Tommy Maxwell and Dick Johnson were in my band. I told the guys, “Listen, we’re goin’ to Vegas, be with Louis. Right away.” They asked me, “Well, how much money?” I said, “Don’t worry about the money!” (laughs) ’Cause I was doing very well financially in New Orleans because of the hit records I’d had. “Don’t worry about the money.” Well…

Fire at the Casbar

Louis Prima, at 44, was a renowned trumpeter, big band leader, singer, composer of the jazz classic “Sing, Sing, Sing” and entertainer known as “the Italian Louis Armstrong.” With a career dating back to the 1920s, and a sound rooted in New Orleans jazz and swing music, Prima was always open to the latest trend, and had downsized to a small combo. The new act, featuring his comic mugging and the smoky jazz vocals of his 26-year-old (fourth) wife, Keely Smith, had opened an engagement at the Sahara Hotel on the Las Vegas Strip. Despite Prima’s past success, his group was not booked into the main showroom, but in a casino lounge, an open-area bar where gamblers slipped in to drink away their blues between losses and performers and dealers gathered after their shows and shifts. Lounge entertainment was usually unobtrusive. Lounge performers were on a lower rung of the show business hierarchy. All that was about to change when Sam Butera pulled into Las Vegas on December 26, 1954.

I came in that evening. And my horn wasn’t there. It was left in Houston. And I had no clothing except the clothes I wore on my back. I called Louis, I said, “Louis, I can’t go on tonight.” He said, “What do you mean you can’t go on? I told you, I been tellin’ all these people that you’re gonna be here tonight.” I said, “I have no horn or clothes.” He said, “We’ll get you a horn. And we’ll get you clothes.”

We went into the Sahara Hotel and there was a lounge they called the Casbar, which was a nice lounge, man. Right on top of the people. And there was a ramp they put from the stage that went over the bar and some steps in front of the bar so we could walk down there and do the march thing (marching the horn section around the room, playing “When the Saints Go Marching In”). People love that. That was always the thing in New Orleans. Every band in New Orleans did the marching thing. It was nothing new that we were creating. They all did it, but these people out here, I guess they hadn’t been exposed to that kind of carrying on, you might say.

It was so wild! It was unheard of to come on a group without a rehearsal, just walk onstage and say, “Here, play the music,” you know? That was a muthafucka, man. But we were sharp enough, our ears were big enough to hear and surmise what he wanted. And right from that moment I saw that the guys would follow me, and I’d add things on, little thing here, little thing there. And Louis was groovin’ and doing different things, like the “answering thing” when he’s playing. He’d sing one thing, and I’d actually play it exact on the saxophone. Like we did on Oh, Marie: “Whatsa matter? You can’t play in Italian?” And it was funny.

(VIDEO: Louis Prima – When You’re Smiling / C’è La Luna / Zooma Zooma / Oh, Marie)

And they were hysterical, he and Keely. Keely, oh I loved it when she sang. I thought she was absolutely a wonderful singer. Her intonation was just fantastic, her phrasing was great and her performance — well, you know their whole thing was Keely not showing emotion and making fun of Louis whenever she had the opportunity to. People would laugh at that. And she’d just stand up there with a blank face and listen. Look at her! And here we are groovin’, knocking our asses off, and she’s just there like she don’t give a fuck.

How the name “The Witnesses” came about, after the first set was over, Louis always acknowledged: “Ladies and gentlemen, may I have, Keely Smith! Sam Butera!” And he couldn’t think of the names of the guys — the two guys. Louis had never met them before we walked on stage! And I said, “The witnesses!” And he said, “The Witnesses!” and then people laughed, and so we kept the name. The Witnesses.

We got offstage and Louis looked at me and he says, “I told you!” And that was it. After the sets, Jesus Christ, everybody was grabbing me, hugging me, the people, the fans in the audience. “About time you showed up!”Kidding me, because I was supposed to come Christmas night, and Louis told them, “He can’t make it.” And the fans immediately enjoyed what I did. They really did, right from the get-go. It was different, a fire, man, under the group. When I got there, fire happened.

The people who were there before I got there were like mamalukes in the audience. Mamaluke is somebody that’s dead. You know, just about dead. Mamalukes. (chuckles) Like you’re dead, like a fucking fish hand. Like nothing.

‘I’ll tell you, he was an incredible entertainer….

He knew show business inside out. I ain’t never

seen a performer in my whole life, nobody, but

nobody can get on the same stage with him.’

– Sam Butera on Louis Prima

Prima had reserved a room for Sam and the boys at the Monte Carlo, an inexpensive motel about a mile down the Strip from the Sahara. But before tucking in, Sam had got first taste of Las Vegas cuisine.

It’s the first time I had ever seen a — not a brunch. What’d they call it? Chuckwagon. Chuckwagon. Where they get a big round of meat and they cut slices off. I think it was a buck and a half. And I said, “Son of a bitch, man, I get me some…” So I used to have chuckwagon every night, trying to save money. ’Cause I came out here, Louis gave me two-fifty. I said, “Oh, shit, man.” He said, “Hang in.” He didn’t give me a raise. Didn’t give me a raise. Didn’t give me a raise. I was making five, six hundred a week, seven hundred a week in New Orleans. He said, “Be patient.” And so I was.

April 19-20, 1956: Making a record

Louis had always wanted to record with Capitol Records. And boy, when they came around, man, when he got that contract from Capitol Records, he was in seventh heaven! They heard about all the noise. L.A. ain’t that far apart from Vegas and they heard fast what’s happening with Louis and Keely and myself. Somebody told them, “Hey, you gotta get this group. They’re tearing it up in Las Vegas.” They sent Doyle Gilmore, who was an A&R man. And he was an ex-drummer. And he heard the group and told Louis, he says, “We would like to record you.” And Louis negotiated with him, I guess, and got it on.

We started getting arrangements together. That’s when we got Gigolo and I Ain’t Got Nobody. Little Red [trombone player Jimmie “Little Red” Blount, another recruit from Butera’s New Orleans band, The Night Trainers] and I were together then. We got the arrangement down. Louis had these two tunes he wanted to do. Just A Gigolo and I Ain’t Got Nobody. So we sat down and screwed around and come up with the chart.

(VIDEO: “Just A Gigolo/I Ain’t Got Nobody”- Louis Prima, Keely Smith, and Sam Butera & the Witnesses)

We had to drive to L.A. Couple new cars, so we drove down there. I was amazed. This round building. Hollywood and Vine. I have never been to L.A. before, except years ago. I saw this, man, I said, “Oh, shit.” I went into the studio and I saw this equipment, couldn’t believe the board they had. That board there was unbelievable, man. And we knew what we were gonna do. We did just what we did onstage. And it came out fantastic.

We did everything, the whole album, in one night. Took us about five hours. The whole album. Oh, they were jumping up and down in the sound booth, you know, digging what we’re doing. And the sound there was like, hot. And they were excited. So was I, after seeing their reaction. But I had been seeing that reaction with the audience, months before I went to the studio with them, so I knew what was happenin’. And just watching how thrilled Louis was that things had a turnaround for him when he was — well, what was he? I would say he was in his fifties then, or late forties when I came on the band (Prima was 45). And he thought that it was all over.

They sent Louis a proof record. Louis told me to come by the house and he played it for me. They were living at Bali Hai Motel. It was right at the side, you might say, of the D.I. (Desert Inn). He said, “Sam, this is us. They finally got us on tape. The sound. The energy. It’s us.” And he was right. Usually people love you, watching you, but to get that same production from just listening to you? They caught it.

The album, The Wildest!, credited to Louis Prima and “featuring Keely Smith, with Sam Butera & the Witnesses,” was released in November 1956.

Immediately the goddamn thing started selling albums like crazy. Oh, everybody’s thrilled for us. ’Cause Vegas was like a family at that time. Everybody knew everybody by name. In just about every hotel, you knew every dealer. ’Cause after they get through work, they’d come in and see us. Guys from Stu [Steubenville, Ohio, well-known for its Mob-run casinos] and all that crowd. Guys from all different areas of the country who came to Vegas to deal. Because where they were from, it was illegal. So they had their own little cliques. “Where’ll we go? Let’s go see Louis and Keely and Sam.”

Actually, we were the hottest attraction in Vegas. We didn’t get to work till eleven, so we worked until four, five o’clock in the morning. Louis used to have the people in the audience going hysterical, then all of a sudden all your performers started coming in. And all the showgirls used to hang in there with us. Used to love that group. That’s when all your main showrooms had a line in front. Line of girls. And of course, after the show, they were told to come sit in the lounge, to pretty it up. You know what I mean? Chicks. We had more fucking broads then. Oh, my God. Man, oh man. Two, three broads a night, man. That was, that was, that was — oh, it was unbelievable.

I never got any money from the records. Louis and Keely made all the money. It was Louis Prima and Keely Smith, you know. But they’d pay me for the record date, and that was it. I didn’t make any royalties. Just for the session. But they were making a lot of bread.

Momo Giancana buys Sam a Jag

Louis, Keely and Sam’s popularity soared once again with the release of the single, That Old Black Magic, which reached #18 on the Billboard chart in December 1958, and won Louis & Keely a Grammy at the first annual awards show on May 4, 1959.

Louis very rarely talked business around us, you know? I guess he figured the less we knew, the better off we were — meaning the less we knew about the business, how much money he and Keely were making, we wouldn’t cause no fuckin’ waves, you know? Asking him for this and ask him for that. Anyway [with ‘That Old Black Magic’] he told me, “Sam, we got ten more years, baby. Because of this fuckin’ hit, this is gonna last us ten years.” I said, “It’s a big record for us.” And he said, “We got some calls.” He said, “We got a call over at the Chez Paree in Chicago, we got a call to work the Copa in New York. And then we come back, we’re gonna go to the Moulin Rouge in L.A.

My man, we went to Chicago in the fuckin’ dead of winter. Snowstormed! There were people in line around the fuckin’ block. It was so fuckin’ cold, I was living two blocks from the club and I had to catch a cab to go to work. That’s how fuckin’ cold it was. People were lined up around the block. Packed the Chez Paree! Mo [Chicago crime boss Sam “Momo” Giancana, who controlled many Vegas casinos] was there. And every fuckin’ hood in Chicago, he told, “Be there!” Every fuckin’ hood in Chicago was there — with their families, not alone! You wouldn’t fuckin’ believe it. Never had that much business in the history of the Chez Paree. No fuckin’ entertainer. And, well, anyway, that was history, boy.

Right from there we drove to New York, played the Copa. Standing room only. No act in the history of Copacabana drew that kind of people. And The Ed Sullivan Show. That was like the show at the time. When you got on The Ed Sullivan Show, you were classified as a superstar.

I bought a Jaguar. 1959. I bought the 3.4 litre four-door. Bought me one of those. I drove that. Me and three other guys. If I tell you who bought it for me — I can’t tell you who bought it for me because of — Sam bought it for me. Sam, uh, Mo. What is his last name? Giancana. He bought it for me. He said, “When you get the money to pay, pay me back.” So when I got back, fifty-five hundred, I think it was, when I got back home, I said, “Well, Louis, I gotta go pay this money,” I said. “Who should I contact?” Somebody else told me, “Mo told me to tell you to give the money to Johnny Drew at the Stardust.” ’Cause Chicago owned the Stardust.

Chicks. We had more fucking broads then.

Oh, my God. Man, oh man. Two, three broads

a night, man. That was, that was, that was —

oh, it was unbelievable.

And when I got to the Stardust, Johnny Drew told me, “Give the money to Keely. Tell her Mo said that’s her Christmas present.” And I said, “Man, I can’t give Keely Smith fifty-five hundred dollars!” I said, “Don’t do this to me!” I said, “Let me give the money to Johnny Drew. If you want her to have it, send somebody to give it to her, but don’t make me give it to her.” ‘Cause I didn’t want to get involved in nothing, man. I think she was making it with him, you know? Then Louis would say, “What’d you give Keely five thousand five hundred dollars for?” What am I gonna tell him? Then he knows. He’s gonna know something’s fuckin’ up. He might of knew it was up then, but it seemed to me they didn’t give a fuck. They didn’t care. And I don’t know how all of a sudden she cared.

And that was 1959. Louis was making a lot of bread. Lotta bread. I still wasn’t a financial part of the act. I was, by that time, making about seventeen-fifty a week, which is good money. That was the most I ever made, was seventeen five.

The Showroom

Louis, Keely and Sam reached the pinnacle of their success on December 29, 1959 when, after six years as the city’s top lounge act, they opened as headliners in the Painted Room, the main showroom of the Desert Inn on the Las Vegas Strip. Prima had negotiated a three-million-dollar deal to star at the D.I. for a minimum of twelve weeks a year for five years. “There was some discussion as to whether or not the transition from the lounge would be successful,” reviewer Duke wrote in Variety. “The answer is obvious — Prima & Smith are better than ever.” Unfortunately, just as Louis & Keely had achieved their dream, their marriage was unraveling. Louis’ philandering had been an open secret for years. Now Keely was carrying on affairs, and neither was attempting to hide them.

“The greatest act in show business!

They have no equals.” – Ed Sullivan

I don’t want to say that Keely started going out on him, and he started going out on Keely.

Well, he saw her. See, that’s the thing. I feel like I’m incriminating myself, and I could get in a lotta– She was always…. she’d make a play for this guy or that guy. It looked innocent. Aw, I can’t mention names. No members of the band. No, just people in the audience who had influential friends. Entertainers, and I don’t know if Louis knew it or not. I really don’t. She made it with so many people, man. It’s unbelievable.

She had been doing it long prior to that. When she was with the big band, she was making it with a lot of guys in the band. Jimmy Vincent made it with her, you know. Whole bunch of guys made it with her. Keely, one night with Bobby Darin, with Sammy Davis, Billy Eckstine, Nat King Cole — you fuckin’ name ’em. Really liked to fuck, that’s all. I was never there when it happened. It was just told to me. To each his own. Didn’t mean nuttin’ to me, ’cause I’m fuckin’ around, too. And you couldn’t say nothing because Louis didn’t want to hear no talk about it. He would just laugh, ha ha, and walk — everything was a joke. Aw, it’s just bullshit, you know. Bullshit.

Keely, one night with Bobby Darin,

with Sammy Davis, Billy Eckstine,

Nat King Cole — you fuckin’ name ’em.

And we all said, “How the fuck can he put up with this shit, her fuckin around like this? Then you think back, well, how can she put up with it? And we all shake our heads. I don’t know, man. There’s a fuckin’ wild situation here. See, the way I surmised it, Louis was a swinger all of his life. That didn’t just start there at the Sahara. That’s bullshit. He had five wives, you know, and he liked, liked, liked ladies. He loved ladies, man, and I guess Keely must’ve not been blind. But he was at least a little discreet. She wasn’t.

She hit on me. I wouldn’t mess with her. But I wasn’t into that. I had my own thing with other broads.

‘Fuck the Kennedys’

On January 19, 1961, despite a major blizzard that knocked out power to most of the city, Louis, Keely, Sam and the Witnesses performed in Washington, D.C. at the pre-inaugural gala for president-elect John F. Kennedy. The show was produced and hosted by Frank Sinatra and featuring the biggest stars of the era.

That night, I got to meet Bette Davis! Everybody was there, man, Everybody you could fuckin’ dream about. And being on the same bill with everybody, being treated like fuckin’ royalty, man. Unbelievable. So after we got through, Louis and Keely were invited to a private party for the Kennedys and all their friends and Nat King Cole and all the fuckin’ superstars. And we [Sam and the Witnesses] weren’t invited, so we were walking around like fucking idiots! And all of a sudden, Piggy, Keely’s brother, came up. He said, “Louis wants you guys to go play for –” I said, “Tell Louis, fuck the Kennedys!” Never went. Fuck the Kennedys. Why didn’t they invite us in the first place? I’m going to entertain for them now? And they didn’t invite me? Fuck ’em. And I didn’t go.

Louis didn’t say nothing. He said, “I don’t blame you.’ He said, “I told ’em I couldn’t find you.”

The final blow

Between engagements at the Desert Inn, Louis, Keely and Sam continued to play top venues across the country. On May 16, 1961, they opened a two-week engagement at the Latin Casino in Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

We were working at the Latin Casino when she caught him. From what I understand, I wasn’t there, she caught him in the parking lot getting head from this Indian broad who was in the line in the show. Louis, I guess he had the hots for her. You know, she was a nice-lookin’ girl. A fine body. And that’s when the parting of the ways came. I don’t know if they had made an agreement that neither one would fuck around anymore, and then she caught him. Somebody squealed and told her, “Go look out in the car.”

I think it was in between shows. She left the fuckin’ stage, never came back. I think she left the next day. Or that was a closing night. I don’t remember what night it was.

Everybody knew they weren’t getting along. Saw it going by the wayside. I mean, they tried to patch it up, I guess, but she didn’t want no more part of it. All of a sudden, she became a saint. And her agent eventually told her, “You don’t need him. He needs you. You don’t need him. He needs you.”

What was I doing? I was just saying to myself, “What’s going to happen now if they break up? They’re going to throw away a thing that they worked at their whole lives for. This is something that they’ve been both wanting. They’re on top of the world!” Nobody knew whether they would stay together and work or she’d go her way he went his, but when it came down to it, when she left and we started working alone the next engagement, I knew right away that he didn’t want to work with her and she don’t want to work with him.

Out the window

Word spread quickly that “the hottest husband-and-wife team in show business” was headed toward divorce. The final D.I. engagement opened on August 4, 1961. Variety’s Duke praised the “Return of the Wildest” show, from the opener, when bass man Rolly Dee did “a very funny bit… with Chinese doubletalk,” to the finale, when Prima introduced a new dance called the Grasshopper, “a catchy step… and a good gimmick for audience participation.” As usual, the band opened with “When You’re Smiling.”

She came back for the last engagement. That was cold, man. You could feel the ice in the fuckin’ air. She’d laugh and he’d be a buffoon, you know, clownin’ and smilin’, and you could feel ice. That was like, doing it down the line, you know. We did two shows, you know. But it was just like a throwaway. There was nothing felt. But the one that they looked like they really enjoyed, was That Ol’ Black Magic. They really enjoyed doing that fuckin’ tune.

(VIDEO: Louis Prima and Keely Smith “Black Magic”)

Let me tell you another story now before I forget. Now, now one day, after the split-up, Keely said, “Sam, you want to come with me?” And I said, “Oh, fuck. What am I going to do here? And I gave her something. I said, “I’ll let you know.” So I started thinking about it, and I said to myself, “If I go with her, it ain’t going to be no fuckin’ good because I knew who was responsible for this fuckin’ act and that was Louis Prima. I called her and I said, “Keely, don’t get angry, but I’m going to stay with Louis.” And I went and told him. I said, “You know, Keely asked me to go with her, but I’m going to stay with you.” He said, “Oh, I was hoping.”

Keely Smith was granted a divorce, on the grounds of cruelty, on October 3, 1961.

We had our new home and we knew Louis was going to get the divorce that day, so we invited Louis and his mother over to the house to have dinner with us. And his mother said, “No, let me cook.” ’Cause Louis loves the way she cooked chicken cacciatore. I’ll never forget. And we said, “Sure, if you want to cook, it’s our pleasure. The kitchen is yours.” So she cooked chicken cacciatore and it was about five-thirty when Louis got back from the divorce proceedings. He got in the house and he cried like a baby. Cried like a fuckin’ baby, man. He says, “It was something we wanted all of our lives, finally had it in the palm of our hands, just threw it out the window. Why? Why?” He says, “I’ll never understand. All my life, this is what I wanted. And what she wanted, too. Now, we threw it out the window. Now, we got nothing.”

His mother said, “Louis, you did it before without her, you can do it again without her.” You know how mothers are. She told him, she said, “All your life, did you need her? You did it yourself, didn’t you? You’ll do it again.” She was a very strong woman, his mother.

Back to the lounge

After they had split up, we were working at the Moulin Rouge in L.A., and that’s when Louis negotiated the contract to go back to the Sahara. Louis went to Stan Irwin, who was the entertainment director, and he said, “We’d like to come back to work for you. Let’s negotiate a deal.” And Stan told him that he had to have a girl singer. That was in the contract. And he’d be glad to have us back there at the Sahara.

So Louis looked for a girl singer. He found Gia. And Christ, we were working, and Gia was an unknown. Nobody knew Gia Maione. So we were working at the Sahara, and when she joined the group, I said to the guys, “Man,” I said, “if this chick gets billing over me, I’m cutting out. I’m through.” And sure enough, that night on the marquee, her name was equal size of Louis’s, top billing over me.

Gia Maione

And it pissed me off. I said, “Louis, I’m coming by the house tomorrow. I want to talk with you.” And I went out to the house up on Warm Springs Road. Keely was gone. He had some friends there. And he said, “Excuse me, I want to have a meeting with Sam.” So we went outside the pool area, away from everybody, and I told him. I said, “Man, this is like a slap in the face. You don’t do this.” He said, “What do you mean?” I said, “The fuckin” marquee.” I said, “I worked too hard all these years, like to accomplish something, and I think I’ve accomplished it, because you’ve helped me, naturally. Then, all of a sudden, Keely is gone — who I respected as a star, just as much as you. Now she’s gone, and here we are the Sahara Hotel, and you bring somebody, who nobody knows who she is, and she has no credentials, and you bring her here and give her billing over me? Not equal billing, but top billing over me. What am I to do?” I mean, you know? So I said, “Best thing for me to do is to leave.”

And Louis ordinarily, I know he would’ve said, “Leave,” but I guess I was too important to the organization, to this group, for him to, I guess, say what he would ordinarily have said. He started talking to me. And talking to me. Things like, “Because of the contract saying that I have to have a girl singer, and I thought it wouldn’t look nice if you were on here and she was on the bottom. It wouldn’t look like it was an act between the girl and I.” I said, “What? To begin with, we don’t need another girl.” He said, “But that’s in the contract. I have no alternative. I have to use a girl.”

(VIDEO: Sam Butera & The Witnesses – You’re Nobody ‘Till Somebody Loves You 1964 with Louis Prima & Gia Maione)

We weren’t going to work the main showroom at the Desert Inn without Louis and Keely. They wouldn’t accept it, I think, with just him alone. So he said, “Well, let’s go back to where we started. Maybe we might get this thing rollin’ again. Get a new face.” But he had a girl singer before Gia, who didn’t make it. I had tears in my eyes, ’cause I was very upset. I said, “Man, I thought you had more love for me than that. After all these years being together, writing all these arrangements and doing this and that, and not even getting fuckin’ paid for ’em.” You know? “All of a sudden, you hire a stranger that nobody even knows in the business? If she would’ve been a star, I’d say terrific man, I understand. But a nobody?”

I said, “The least you could’ve done, before you put her up on the goddamn marquee, would be to come to me and explain to me what you’re gonna do. Don’t make me look like a fuckin’ idiot!” And he says, “Well, I didn’t mean it to be that way. I’ve got so many things on my mind.” And he started telling me, “Look, Sam, be patient.” You know. “One of these days, you’re going to be a star. You’re a gem. You’re very val–” All this bullshit. I said, “Bullshit, Louis. You’d have taken time if I was that important to you.” And he kept talking and talking. He had a way, you know.

Sam Butera at the Tropicana, Las Vegas 1989.

Sam Butera stayed with Louis Prima and Gia Maione. He stayed after Prima married Gia; after Gia left the act to raise their two children; and into the 1970s, when he and Louis added Sympathy for the Devil to their set. Louis Prima underwent surgery for a brain tumor in 1975, fell into a coma and died in 1978. Sam Butera renamed his band The Wildest (he said that Keely owned the name “The Witnesses”) and carried on with the act in casino lounges and nightclubs for another 25 years. He paid tribute to Louis Prima every night, opening each set with When You’re Smiling and closing with When the Saints Go Marching In, leading the horn section on a stroll through the audience, slapping palms, shaking hands, and somehow continuing to blow that saxophone, as always, with a smile on his face. Sam Butera died on June 3, 2009. He was 81.

Before I even joined him, he was always a hero in my eyes. I loved him. “Cause I’d listen to his records. I used to do some things of his, you know. I can never get Louis’s sound, but I knew that right phrase, you know? I’ll tell you, he was an incredible entertainer. I watched him work that first night, because I consider myself a hard worker, too. He worked hard, but he had it coming, man. He knew show business inside out. I ain’t never seen a performer in my whole life, nobody, but nobody can get on the same stage with him.

How was he different offstage?

Business. Business.

≠≠≠

Bonus Video: Louis Prima & Sam Butera – Coolin’

BURT KEARNS produces nonfiction television and documentary films. He wrote the books TABLOID BABY and, with Jeff Abraham, THE SHOW WON’T GO ON: THE MOST SHOCKING, BIZARRE, AND HISTORIC DEATHS OF PERFORMERS ONSTAGE.