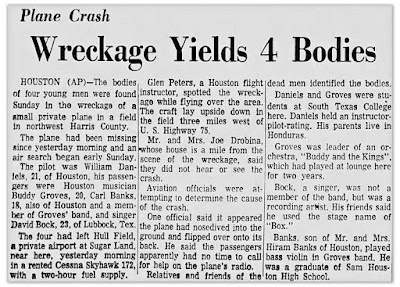

DONATO DI CAMILLO FOCUSES ON THE KRUSTIES

New York’s leading street photographer meets the Krusties, grunge-style, modern-day nomads

November 28, 2018

photo © by Donato Di Camillo

by Burt Kearns

All photos © by Donato Di Camillo

You can find them in just about every major American city. Many are not much older than teenagers, huddled together, hanging out near the train station or shopping district, on the boardwalk, on the sidewalk. They’re dirty, unwashed hair soldered into dreads. They’re marked with tattoos, mostly non-pro, often across their faces. They’re homeless, right? But not the typical “homeless” the term implies. Not mentally ill or brother-can-you-spare-a-dime homeless. They’re young, a little scarier. So you ignore them, maybe make a quick detour to the other side of the street. Donato Di Camillo did not.

Donato Di Camillo takes photographs. In a little over five years, he’s risen to the top ranks of street photographers, not only in his native New York City, but around the world. He first made a splash with in-your-face flash-color portraits of people on the Coney Island beach and boardwalk: the mother in the burkha in the water, the wrinkled old ladies, the fat people in the sand, the crazy derelict howling at the wind while a seagull hovers overhead. The photos were raw, vivid, alive. This was not Miami Beach.

Next came searing black and white portraits of the mentally-ill homeless. All people on the fringe, outcasts, hard stuff to look at until you realize the artist is drawing you in. You’re not looking away. Not sneering.

“I think I empathize with people because I know

what it’s like to have been judged. Obviously, I’ve

been locked up, or categorized growing up for

hanging out with the people that I hung out with.”

Di Camillo’s work got him immediate attention, but it can’t be denied that a big reason he smash-cut onto the art scene was his backstory. A kid from Brooklyn who was in trouble from the start, he studied photography — the story’s familiar now — while serving three years in a federal prison for his role in a Goodfellas-style Colombo crime family heist conspiracy. He honed his camera skills during two years of home confinement. When he was freed in 2011, he returned to his mean streets, this time looking not for trouble but to connect with the ones most everyone else looked past.

Di Camillo swiftly outgrew the backstory as his work got bigger and his scope expanded to include reportage, video documentary (when I first met him, he was filming a study of a community of rats — not Mob squealers, but actual squeaking vermin in a wall), and commercial branding. He’s also led workshops and accepted assignments and projects around the world, including the Deep South, Texas, Arizona, Mexico, Italy and Havana. It was during these travels that he noticed and began to document an underground punk subculture across the country, steeped in American rebel and hobo traditions. Meet the Krusties.

“People spell it different ways,” Di Camillo tells me. “But the guys that I know, they spell it with a K, ‘Krusties,’ like Krusty the Clown on The Simpsons.”

PKM: So who are they? Who are the Krusties?

Donato Di Camillo: They’re a bunch of grunge-style, modern-day nomads. They’re a punk movement. Most of them are tattooed on their faces, and they ride the rails. They hop the rails from state to state, to where it’s warm. Like, say if they’re in New York, as soon as it gets colder, they’ll jump a freight train back to California or into the warmer climates somewhere. They live off people’s handouts. They’ll hustle. And they’ve grown. Over the past couple of years that I’ve known them, I see them growing in numbers.

PKM: Where did you first notice them?

Donato Di Camillo: Union Square Park was where I first met them. The park on Fourteenth Street in Manhattan. I met this girl Jessica. She was beautiful, a gorgeous girl, but she was really, really grungy and dirty and, well, I was taken aback by her looks. That was the first time I photographed one of them. And I asked her what the deal was, what this movement was about. And I found they basically believe in non-compliance. They make their own rules. They’re not for any kind of government. They’re anti-establishment, basically rebels.

PKM: I’ve seen them in L.A., on the Venice boardwalk, in Santa Monica.

Donato Di Camillo: They’re very easy to point out. Usually they have a pet rat or a dog with them. They travel with these animals. They’re kind of like companions — and I think it helps with their hustle. You know, people empathize with the dog more than with humans sometimes. And they’re willing to help out the dog and throw them some change.

PKM: Do they all live on the street?

Donato Di Camillo: Yeah, basically. Most of them. If they’re not living on the street, they’re living in subway shelters or public housing. But they never do for long. They’re hopping trains, constantly moving around. Most of them find a comfortable place, like in Coney Island, where I ran into Jessica again. This time she was with about ten or twenty of them. They all shared cigarettes and liquor. Whatever they do, they all make sure look they after each other. But as far as working or anything like that, I’ve never seen any of them do any kind of work.

PKM: What’s the age range?

Donato Di Camillo: I think the oldest one that I met was probably around forty-seven, forty-eight. The youngest, God, probably seventeen.

PKM: Teenage runaways?

Donato Di Camillo: Yeah, most of them are. The stories that I’ve heard are incredible. I’ve taped a number of them. Some have been victims of incest, from fathers and mothers. I’m always very inquisitive about what makes them tick and why they do what they do. So I’ve found out through a lot of encounters that a lot of them drink because they’ve been molested. Others, there’s something tragic that occurred in their lives. A lot of them come from these middle-American towns that are very poor and the per capita is very low.

PKM: So the Krusties are more like a nationwide community?

Donato Di Camillo: Look. I’ve been on assignments that’ve taken me to Georgia, and I’ve run into people that I met here in New York and San Antonio, Texas. I met this one guy, Mark, and I showed him photos of a few Krusties that I’d met back East. And he was like, “Hey, I know all these guys.” They’re all friends, and it seems to be a really big network. They’re spread out all over the U.S.

PKM: Are they a product of tough economic times? Or would they be around anyway, like hobos once were?

Donato Di Camillo: Nah. I don’t think they’re part of a tough economy, because, for me, I believe if you really want to work, you could find some type of work, whether it’s as a dishwasher or working at a carnival. Any work is work if you need the money, but it seems that they just don’t want to. I mean, they tattoo their faces. I’ve got a photograph of a guy who had “Fuck society” on his forehead, for crying out loud. How are you going to get a good job with those words on your face? (laughs)

PKM: Yeah. You can’t work the counter at McDonald’s with a ‘fuck you’ tattoo on your face.

Donato Di Camillo: Look, we’re all judgmental. I think we’re all raised a certain way, and I think that we’re raised to judge people by their looks, obviously. Let’s face it. Magazines don’t portray people that are down and out. And so when I first encountered them, I was guilty of it myself. I mean, it’s not even the fact that they live on the street. They don’t wash. The women, a lot of them, don’t shave under their armpits. They don’t change their clothes. They don’t take care of themselves. I’ve seen staph infection and liver disease. I’ve seen one kid, throw up, I’m talking about pints of blood, right in front of me. But with that said, when I got to know them, I found they’re not dumb by any means. They’re intelligent. A lot of them are big readers. They read a lot. They’re not bad people, but they’re on their mission. I don’t know what their mission is, but I think a lot of them are running from who they really are or what’s happened to them.

PKM: So you say you’re judgmental, but still you approach them. How do you get their confidence?

Donato Di Camillo: I’ve become really good at approaching people, because I’ve always dealt with all different types. I grew up on the streets, just in a different sense. I grew up with all kinds of tough guys and all kinds of characters, if you will, so being on the street, and being on the defensive, I had to learn how to read people and how to navigate around bad situations. So I learned how to approach certain people. In this case, I make myself known by maybe giving them a dollar or some change. And after a while, I’ll kind of establish a relationship slowly. And then I dig in and find out exactly what’s going on. I’ll share a little bit about me. That always helps. And that’s where the trust starts.

PKM: You seek out and meet people on the fringe, the people who seem to be down and out. Why do you have that empathy? Is it because of how you grew up?

Donato Di Camillo: I think I empathize with people because I know what it’s like to have been judged. Obviously, I’ve been locked up, or categorized growing up for hanging out with the people that I hung out with. I made some bad decisions, and I know what it’s like when people stare at you or look at you and think, ‘Hey that’s the bad guy.’ So in that sense, I know what it feels like. Being in their shoes, I could never understand fully, but our feelings are all similar. For instance, I don’t know what it’s like to be raped, but I know how it feels to feel hurt and pain and that kind of emotional distress. So, I can empathize with anybody, because we all are human beings, and we all share that commonality.

PKM: You’ve been in in the national spotlight, the international spotlight, for what? About four or five years?

Donato Di Camillo: Yeah. Roughly, I guess. About five years now.

PKM: So, one of the reasons that you probably got attention from the media initially is because you had this great little backstory that could be told in a couple of sentences. “Here’s the goodfella who went to prison and learned how to be a photographer. And then he practiced while he was on house arrest and then he came out.” And that was a good tag to start with in your career. But do you feel like you’re kind of past that whole ‘backstory’ story? That you’ve grown bigger than that?

Donato Di Camillo: I was past it when they brought it up! I just didn’t think it would be so sensationalized. I mean, for me, really, who gives a fuck? (laughs) I didn’t think it was a big deal. I mean, for crying out loud, 18th Avenue where I grew up, it wasn’t odd for me to see John Gotti or Sammy the Bull and these guys walking around. My friends used to wash their cars when they were kids. It was like something out of Goodfellas, really. And you’d see bodies pop up in the streets. It was like that. So for me, it wasn’t that unusual ’til they ran it, and I said, “Really?” People made such a big deal out of it. I didn’t think that the backstory was so sensational. But obviously people thought it was.

PKM: And the art crowd always loves that little bit of danger. That’s good.

Donato Di Camillo: I like danger. (laughs) I still like danger. (laughs again) But I just like to do it legally these days.

PKM: Now, again, you’re on house arrest or home confinement, and you start out very, very micro with the camera, shooting spider webs and raindrops, and whatever you can find on your property. What led you to people? What led you to street photography?

Donato Di Camillo: Somebody told me, “Shoot what you know.” An old timer, he wasn’t even a photographer. I was locked up. I remember sitting on the bleachers. I used to hang out with this old man. I like the old-timers; they always had the best stories. So I was like, “You know, I think I want to try this photography thing out. I liked it before I went in and once I get a chance to get out, I wanna try it. I just don’t know what the fuck I’m going to shoot.” And he was like, “If I was you, go home, and do what the fuck you want to do. Shoot what you know.” And I said, “What do I know? The only thing I know is the fucking streets.” And he told me, “Then shoot the fucking streets.” And then that’s exactly what I did.

PKM: You know a lot about the history and the great photographers. Who are your major influences?

Donato Di Camillo: Some of the great influences for me were (Sebastião) Salgado — his work is incredible — and the real gritty photographers, Bruce Gilden, Diane Arbus and Robert Frank. There’s so many.

PKM: You mentioned that you met Bruce Gilden at one point.

Donato Di Camillo: Yeah, Gilden I met in a snowstorm. We were like the only two nutjobs. He’s kind of a whacked-out guy, he’s pretty blunt, and you could tell he don’t pull any punches. I ran into him in what is now my friend’s store in Manhattan. And for me it was like seeing Frank Sinatra! I was like, “Holy shit, you’re fucking Bruce Gilden.” And he goes, “You know who I am?” I said, “Yeah, I know who you are. I read about you in prison.” And he goes, “In prison?” And he liked that. He had a kind of fucked-up childhood as well, and we were talking a while. He gave me some advice, to take bits and pieces from work that I like and make it my own. I was trying to imitate him for a bit but I realized that I can’t be anyone else but who I am.

PKM: When people look at some of Gilden’s work, or Diane Arbus, they might say, “Oh my God, look at those freaks.” But your work takes people who are on the fringe and who might be considered freaks, and draws the viewer in. You see their humanity. The viewer is not put off by them.

Donato Di Camillo: Well, I believe that the viewer should feel the photograph. It should be something that evokes feeling and emotion. I’m not a critic by any means, and I’ve only been in this game for a very short time, but with that said, I made a little bit of a mark. And I think that these days, it’s very difficult to find something that’s fresh and different and new and with a different approach. People aren’t looking for the same old shit. I can’t be Cartier-Bresson, just like somebody can’t be me.

PKM: When you’re out on the street, is it just you and a camera?

Donato Di Camillo: I usually got a camera and maybe an extra lens, that’s it. I don’t carry anything heavy, unless I go on assignment, when I don’t know what the hell I’m going to expect. If I need a little more reach, I’ll carry a longer lens. I’ll bring a couple of lenses and some light, you know. Depending on the assignment, sometimes I need help, an assistant with me to hold a light or maybe to just hold my fucking bag. (laughing) Because it gets in the way! So yeah, sometimes I need an assistant just to hold the light or just do my editing, while I keep working.

PKM: When you lead your workshops, what’s the one most important thing you could say to somebody who wants to start up in photography?

Donato Di Camillo: I think it’s important to be yourself and I think it’s important to have respect for people. Be yourself and have respect for whoever you’re creating the story on or you’re creating work on with. It’s important to have that respect because if they sense that you’re not being genuine or you’re being one-sided, you’re not going to get what you’re looking for. They’re gonna withdraw and their face is not going to look right or their eyes won’t hold the photograph. You have to have the ability to have them drop all their defenses. And if you’re a street photographer and you’re in a strange country, people don’t know who you are, so you better be good at what you’re doing. And the only way that a person could be really good at what they do is if they really be themselves and they’re really honest about who they are and what they’re doing.

Any work is work if you need the money, but it seems

that they just don’t want to. I mean, they

tattoo their faces. I’ve got a photograph of a guy

who had “Fuck society” on his forehead, for crying

out loud. How are you going to get a good job with

those words on your face?

PKM: What’s next for you now? What’s your next project?

Donato Di Camillo: I’m going to Disneyland! No, I’ve been asked to do a couple of assignments. I’m working on something, I don’t know if I can say where it is. The town’s in a red state and the politicians there are trying to push low-income people out by holding back jobs and outsourcing them, basically because they don’t want them around. It’s a tourism town and they’re bad for business. There’s even Krusties down there. I was called by a foundation to shed some light on the injustice. I’m known for that. I’m going to go there and I’ll be photographing the situations and reporting what’s really going on. I understand about making money, but this is a lack of human decency. You have to make money, but there’s also people dying on the street there.

PKM: All right, man, thank you for this. And getting back to the Krusties. Are they into music?

Donato Di Camillo: Oh, yeah. I’m not familiar with a lot of the music, but they’re into that heavy thrash kind of punk. Even the Ramones, the older stuff, they’re into all that really hard punk music.

PKM: What kind of music are you into? You into music at all?

Donato Di Camillo: I like it all the way down to classical music. I like all music as long as it’s good music. (laughing) I don’t know what good music is anymore. I haven’t heard good music being made in probably, twenty years maybe. Not anything that I would say was good, anyway. I like jazz. I like Johnny Cash. Frank Sinatra once in a while. You know, it depends on the mood, I guess.

Donato Di Camillo’s instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/donato_dicamillo

Twitter: https://twitter.com/donatodicamillo

Website: donatodicamilllo.com

Burt Kearns wrote the book TABLOID BABY and produces nonfiction television and documentary films. BURT KEARNS & JEFF ABRAHAM have written a book about performers who died onstage. THE SHOW WON’T GO ON will be published by Chicago Review Press / A Capella Books in September 2019.