WHO WAS KILLING

THE COUNTRY STARS?

STRINGBEAN,

THE GRAND OLE OPRY MURDERS

AND NASHVILLE’S

DAYS OF FEAR

Lost in the shadows of the Watergate hearings and disco fever, four grisly murders riveted and terrified Music City USA, rekindling a wave of paranoia reminiscent of the Manson Family killings

December 19, 2018

by Burt Kearns & Jeff Abraham

When the Hee Haw and Grand Ole Opry star “Stringbean” and his wife were murdered at their home outside Nashville, Tennessee in November 1973, the story made national news. Then, it was quickly lost in the shuffle of Watergate, Skylab and the kidnapping of J. Paul Getty III.

In and around Music City, though, the hillbilly homicides were only the beginning. Not many days later, another Opry performer and his lady friend wound up dead in a pool of blood with bullets in their backs, and Nashville entered a period of fear that could only be compared to Hollywood in the days following the Manson murders. It was a time from which the city, and music scene, never recovered.

Stringbean was Dave Akeman, the long, tall, sad-faced virtuoso banjo player and country comedian who made himself look even longer, taller, and stringbeanier by wearing a costume of a shoulder-to-ankle shirt tucked into a little short pair of blue jeans belted way down below his knees (so he looked like he had an extra-long trunk and tiny little legs). Born in Kentucky, Stringbean was one of the best clawhammer banjo pickers ever. He’d been a country music star since he joined the Opry in 1942, playing with Bill Monroe. He’d been a bona fide national star since 1969, as part of the cast of the television variety series, Hee Haw.

Everybody in Nashville knew the stories about Stringbean. You see, even though Stringbean was most surely a millionaire, he lived in a tiny little cabin on the top of a hill like some kind of hillbilly. His only extravagances, if you could call them that in 1973, were a color television set and a Cadillac car. Stringbean bought a new Cadillac every year, and he paid cash. Not that he knew how to drive. His wife Estelle drove him everywhere. Stringbean and Estelle were known to flash wads of green when they came into town. Word around Music City was that Stringbean didn’t trust banks, not since so many of them failed during the Depression. Any money he had, folks guessed, he carried around on his person. Or, they figured, he kept piled up in his cabin. Stacks of money. Maybe in the walls. Maybe under the outhouse. Maybe millions.

Stringbean and his wife Estelle

On Saturday night, November 10, 1973, fifty-eight-year-old Stringbean performed at the Grand Ole Opry downtown at the Ryman Auditorium. After the show, Estelle, who was sixty, packed Stringbean’s banjo and costume into the back of the Cadillac, and drove him home to their three-room cabin, tucked away on 142 acres at 2308 Baker Road, just outside Ridgetop, north of the city. It was just another night, until the next cold and frosty Sunday morning, when Stringbean’s neighbor Louis Marshall Jones arrived to pick him up for a hunting trip in Virginia. Jones was well known, too. He was Grandpa Jones, a banjo player and old timey singer who often performed with Stringbean at the Opry. On Hee Haw, he and Stringbean were joined at the hip.

Grandpa Jones encountered Estelle’s dead body in the weeds, next to the driveway about twenty yards from the front porch. It looked as if she was running away when somebody shot her in the back. Stringbean, covered in blood and also shot dead, was face-down, inside the house. Stringbean’s banjo, a priceless instrument willed to him by the legendary Uncle Dave Macon, was on the porch.

“This is so sad. Why would anyone want to harm String?” Opry star Roy Acuff pleaded when he and others arrived at the scene. “He was such a gentle guy, always helping others. Money, I guess. That’s why they did it. Look at that little house. That’s the way String wanted to live. He could have bought ten farms that size, with ten mansions on them, but he preferred to fish, hunt and sit in that rockin’ chair and look up at the mountains.”

Roy Acuff said that Stringbean’s killers should be strung up.

Police said the motive surely was robbery. The cabin had been ransacked and some of Estelle’s things were missing. There was evidence that there may have been three killers, since the fatal bullets came in three different calibers. A bullet hole at the back of the cabin indicated Stringbean may have gotten off some shots himself. He was known to carry a gun in his car, but police couldn’t find it. Odd, though, with all that talk about Stringbean not trusting banks, that detectives found seven bank books in the cabin. All added up, they showed that Stringbean had entrusted the bankers with more than half a million of his dollars.

Odder still, after police were done and Stringbean’s body was carted off to the funeral home, the mortician found $3,500 stitched into his overalls. When they cut the brassiere from poor dead Estelle, her breasts and $2,200 spilled out. Seems the police, and whoever shot up the couple, overlooked the $5,720 they were wearing.

Tuesday night, November 27, seventeen nights after Stringbean and Estelle pulled their Cadillac up to their cabin for the last time, police were called to Milson Alley near the intersection of Jo Johnston and 12th Avenues in North Nashville. The body of fifty-five year-old Jimmy Widener was sprawled out in the brush near the alleyway. Splayed across his legs was the body of Mildred Hazelwood. Both had been beaten up and shot from behind, twice, he in the back and neck, she in the back and head, with a pistol, execution-style.

“From the angle of the bullet wounds, it appears they may have been forced to lie on the ground before being shot,” Metro Police Lieutenant Tom Cathey told reporters. “Robbery was the motive, but I won’t say what (was taken).”

Mildred was forty-seven, the widow of performer and songwriter Eddie Hazelwood. She lived in Laguna Hills, California, a long way to travel to wind up dead atop Jimmy Widener’s legs. Jimmy was a guitar player. He’d been a resident of sunny California himself, but that was more than thirty years earlier, when he played with cowboy singers Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. He’d been in Nashville since the early 1940s, and for the past ten years, played rhythm guitar with The Rainbow Ranch Boys, the backing band for country star and Opry regular Hank Snow.

disabled in your browser.</div></div>

The story emerged they were just friends, if that. Mildred had come to town to sell some songs and unreleased recordings from her dead husband. Jimmy was thinking of going solo. They were walking to the Holiday Inn, where Mildred was registered, when The Reaper approached. No wallet or purse was found with the victims, so the robbery theory sounded right. Even so, Bud Wendell, manager of the Opry House, exhibited a big case of the willies. “Killed? I can’t believe it!” Wendell said he’d seen Jimmy Widener on his last day on earth, “right here at the Opry House, meeting with artists, promoters and bookers.”

“First it was Stringbean — a good guy. Now it is Jimmy Widener — a good guy,” Hank Snow said. “I wonder when it’s going to stop.”

Eighteen days, four corpses, two of them Opry performers killed after visiting the Opry. Who was killing the country stars? After Stringbean and his wife were murdered, Nashville stars made sure to lock their doors. In wake of this latest countrified double murder, country music greats, like the movie stars in the canyons and hills of Hollywood four years earlier, hired security, added extra locks to their gates, slept with a gun under the pillow. Everybody, from Roy Acuff to Tex Ritter to Bill Anderson, wondered who was going to be next.

They wondered for a few days, at least. On Thursday, November 29, two nights after the Widener and Hazelwood bodies were found, Lt. Harold Woods and three other Nashville Metro detectives led a raid on the Cayce Motel in South Memphis. They took two suspects outside the motel into custody, but when they went inside to arrest a third man, he started shooting. The cops unloaded their firepower, lobbed in some tear gas for good measure, and managed to clip Maurice McKinney Taylor in the chest as he tried to flush credit cards and jewelry down the toilet. Taylor was thirty years old. They took him away, along with the two others, twenty-four year-old Richard Benjamin Dunn and Phillip Glen Mason, twenty-three. The trio had come all the way from Los Angeles.

Once they carted them to the Memphis jail, the cops called Memphis Gas Light & Power to dismantle the toilet.

On Saturday, Taylor, Dunn, and Mason were charged in the deaths of Jimmy Widener and Mildred Hazelwood: two counts each of murder, armed robbery and auto theft. The Nashville detectives lugged seven packages of evidence out of the motel, including jewelry, credit cards, the alleged murder weapon (a 9mm pistol), and in Mason’s pink suitcase, the keys to Jimmy’s turquoise and black 1966 Lincoln Continental. Memphis cops found the Continental nearby, and said the killers had driven it from the murder scene.

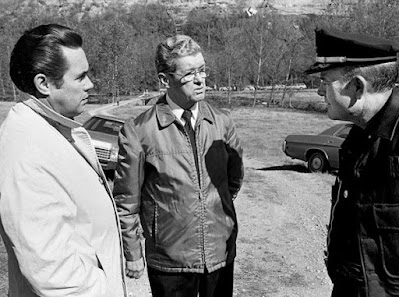

Lt. Woods and Det. Sgt. Luther Summers loaded the shackled prisoners into a car for the ride to Nashville. Det. George Warren drove a car loaded with evidence, and Det. Harold Hamm got to drive Jimmy Widener’s Continental back for more tests.

News of the arrests of three black men for killing Jimmy Widener and Mildred Hazelwood, twenty days after the Stringbean murders, did little to calm the paranoid stars of Music City U.S.A. It was determined that the trio had nothing to do with the Stringbean murders. Whoever killed Mr. and Mrs. Stringbean were still out there, and no one knew when they’d strike again. The calendar page turned to a new year and it looked like the police were making no progress. The reward money added up to $25,000.

The story hit the wires on the seventeenth day of 1974: “Four men, including three brothers and a cousin, were arrested Wednesday on charges of killing David ‘Stringbean’ Akeman…”

John A. Brown and his cousin Marvin Douglas Brown, both twenty-three, were charged with two counts of murder. Marvin’s brothers, Charles Brown, thirty-one, and twenty-six year-old Ray Brown, were charged as accessories to murder, and with receiving and concealing stolen property.

These weren’t African American invaders in the — with all apologies to Charley Pride — pristine cracker lily white home of country music. These were rednecks, local yokels, Stringbean’s neighbors, raised in Greenbrier, a few miles from his cabin. They grew up hearing stories of the Opry star and his caches of cash, and the visions proved more intoxicating than George Jones’ White Lightnin’, so much so that they were willing to kill for a slug.

The arrests were the result of a “sixty-seven day, around-the-clock investigation,” Assistant Police Chief Donald Barton announced. “A long, drawn out investigation,” acting chief Joe Casey said. “We have been gathering evidence practically from the time this happened until today.” The police said the Browns knew they were under surveillance for quite a while, but none made a move to get out of town.

According to the police, cousins Marvin and John Brown had been inside Stringbean’s cabin for hours, waiting for the star to return from the Opry and lead them to the cash. The Cadillac pulled up, and Stringbean went inside, where he confronted the country cousins. There may have been a scuffle. The cousins got the drop on Stringbean and blasted him in the living room. When Estelle realized what was happening, she turned and ran toward the Cadillac. She begged for her life. She was shot three times.

Police wouldn’t reveal the evidence but said some of Stringbean’s money had been recovered. (It turned out the thieves made off with some guns, a chainsaw, Estelle’s handbag, and $250 they fished out of the front pocket of Stringbean’s overalls. They left the Cadillac and drove off with Stringbean’s station wagon, which they dumped.)

Six months later, on July 23, 1974, Nashville Police Sgt. Sherman Nickens waded into a murky pond near Greenbrier. He was accompanied by a reporter and photographer for the Nashville Banner and suspect John Brown. Cousin Marvin told police to search there, promising they’d find evidence. The sarge fished out a rotting vinyl handbag. Like O.J. Simpson’s Louis Vuitton bag would be twenty years later, this bag had been the subject of an intense search by investigators.

Inside the bag were $3,300 in uncashed checks, two recording tapes, some Hee Haw scripts, Stringbean’s crushed straw stage hat, his horn-rimmed glasses, and most tragically and damning to the Brown clan, his costume, that one-piece set of long shirt connected to those tiny midget pants that made Stringbean look like such a stringbean.

On Monday, October 28, 1974, close to a year after the reign of terror, Nashville’s Trial of the Century got underway downtown in the Davidson County courthouse — or to be more accurate, the Trials of The Century got underway. There were two of them, simultaneously. The accused murderers of Mr. and Mrs. Stringbean were in the courtroom of Judge Allen R. Cornelius. Criminal Court Judge John L. Draper presided over the trial of three men accused of killing Jimmy Widener and Mildred Hazelwood.

Security measures at the courthouse were unprecedented. Metal detectors, like the ones they used at airports, were at the entrance. Sheriff’s officers were working overtime. Briefcases, shopping bags, camera bags and any other “unnecessary objects” were banned from the courtrooms. “Our number one fear is Brown against Brown,” Sheriff Fate Thomas told a reporter. “Our second fear is the irate spectator.” Their third fear were black militants. The Widener suspects were believed to have a connection.

Two Nashville television stations were broadcasting live reports from the corridor outside the courtrooms. An attorney for Marvin Brown complained about the circus atmosphere.

Nine men and three women were empaneled for the trial of Marvin and his cousin John Brown. The first witness was Grandpa Jones. He testified that the night of the murder — and Stringbean’s last performance at the Grand Ole Opry — he and Stringbean had made plans to go grouse hunting in Virginia. When he arrived at Stringbean’s cabin the next morning, he found Estelle’s body in the front yard. She was covered in frost.

“I ran to the house, opened the storm door, looked inside and saw Stringbean lying face down in front of the fireplace in the living room,” Grandpa testified.

After Grandpa left the stand, Marvin Brown surprised everyone by pleading guilty to killing Stringbean, but not Estelle. When his co-defendant was asked to enter a plea, he said not a word. John Brown said he didn’t even remember being at Stringbean’s cabin because he was so whacked out on booze and drugs that night.

There was equal hubbub in the neighboring courtroom. Two of the men who were originally charged with two counts of murder were allowed to plead guilty to being accessories after the fact (the police just couldn’t place them at the murder scene). Judge Draper sentenced them both to four- to seven-year terms, leaving Maurice McKinney Taylor, the one who shot it out with cops in Memphis, to face murder charges alone.

A celebrity witness led off the testimony here, as well. Hank Snow said he paid his guitarist Jimmy Widener $400 a few days before he was murdered. A waitress at the Pitt Grill testified that Taylor entered the joint while Jimmy and Mildred Hazelwood were dining there. She said she recognized the suspect because she’d argued with him earlier about a sandwich and glass of milk he’d scarfed down, but claimed he hadn’t ordered. This time, she said, Taylor didn’t order anything. He left the eatery at 9:40 PM and walked south, in the direction of the Ramada Inn. Jimmy and Mildred left ten minutes later. They walked northeast, toward the Holiday Inn. A civilian identification technician in the Metro Police Department with the classic country music name of Jimmie Rogers testified that Taylor’s thumbprint was found on a drinking glass in Mildred Hazelwood’s room at the Holiday Inn.

That thumbprint, Assistant District Attorney John Rodgers said in his summation, proved that the suspect approached the couple as they were about to enter Mildred’s room, and followed them in. “This man was so callous that not only did he rob them, but he had a drink in that room!” he thundered to the jury, as Maurice Taylor smiled thinly. “Fearing the alarm would be sounded before he could leave the motel,” the prosecutor theorized, Taylor then forced the couple into Widener’s car, and made the guitar man drive three blocks to Milson Alley.

“He told them to stand outside in the cold, wet alley, with their backs to the car. The defendant slid across the seat and took his position in the driver’s seat. At that point, the defendant executed Mr. Widener. Then he executed Mrs. Hazelwood.”

Metro Detective R.C. Jackson testified about finding the bodies. He said he removed “a few dollars” in cash from Mildred’s coat pocket, and he removed her Holiday Inn motel room key — from Jimmy Widener’s pocket. That last detail raised an eyebrow or two, but it had no bearing on the murders.

A major difference between these Trials of the Century and ones to follow was their swiftness. In the Stringbean trial, the defense took a little more than a day to present its entire case. One witness was John Brown’s wife. She testified that her husband was “moody and quiet” when he returned home at one AM, the morning after the murders. “I asked him if he was all right,” she testified, “He said, ‘Yeah, I guess.’ I didn’t sleep well. I knew something had happened.”

The following afternoon, she said, John took her aside and told her, “‘We robbed somebody last night and it’s some important people. We went to rob Stringbean and they’re dead now.’ I asked him why. He said, ‘I don’t know why. Stringbean came in shooting and Doug said I killed him and that’s all I remember.'”

That couldn’t have helped the defense much.

The case against Maurice Taylor went to the jury on Thursday, Halloween. Taylor’s public defender had asked on Wednesday that the trial be delayed just 24 hours so he could get a fingerprint expert in from New York City to challenge Jimmy Rogers’ thumbprint ID — the lynchpin of the prosecution’s theory. The judge said “No.” The jury — also nine men and three women — deliberated for a little over three hours before coming back with a guilty verdict. They recommended two life terms, to be served concurrently.

Three days later, the Stringbean jury also deliberated for a little over three hours. On Saturday, November 2, they came back with a verdict. John A. Brown Jr. and Marvin Douglas Brown were both guilty of first-degree murder. The jury recommended 99-year sentences on each of two counts. They, too, asked that the sentences be served concurrently, but Judge Cornelius decreed that the terms would run consecutively. That could put the Browns away for 198 years.

The trials were over. The juries were dismissed. The convicted men were sent away to prison. Nashville, once a music capitol whose stars pretended to be ordinary folks and where everyone felt they were part of a big small town, changed. It was never quite the same after the murders of Mr. and Mrs. Stringbean, Jimmy Widener, and Mildred Hazelwood.

##

Grandpa Jones performed his last Grand Ole Opry show on January 3, 1998, at the Grand Ole Opry House in the Nashville suburbs. He was backstage, on his way out the door, when someone stopped him for an autograph. According to Louvin brother Charlie, Grandpa made one last attempt at a joke, saying, “It looks like I’ve hit a snag.” Then he hit the floor, victim of a stroke. Several more strokes followed. Grandpa was placed in the McKendree Village Home Health Center in Hermitage, Tennessee on February 10. He died there nine days later, age 84.

Marvin Douglas Brown died of natural causes in Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary in 2003. He was buried in the prison graveyard. His cousin John Brown was released on parole in 2014. It’s not known what became of Maurice Taylor. His victims were not so famous.

One last note: In 1996, the most recent owner of Stringbean’s cabin noticed that one of the bricks in the chimney was loose. When he removed it, he found a hidey hole with twenty thousand dollars in cash stashed inside. The money was so badly deteriorated it wasn’t usable. It’s not known how much more had rotted away. Stringbean had hidden away his money in his cabin, after all.

##

The Akeman Family hosts the Stringbean Memorial Bluegrass Festival at Stringbean Memorial Park in Tyner, KY. The 23rd Annual Festival will be held on June 20-21-22, 2019

##

BURT KEARNS wrote the book TABLOID BABY and produces nonfiction television and documentary films. BURT KEARNS & JEFF ABRAHAM have written a book about performers who died onstage. THE SHOW WON’T GO ON will be published by Chicago Review Press / A Capella Books in September 2019.