THE LATE GREAT JOHNNY ACE

Burt Kearns

June 27, 2018

Johnny Ace died at 25, allegedly during a game of Russian Roulette. The legend of his death not only obscures his talent but is built upon a misreading of what really happened backstage that Christmas night in 1954

by Burt Kearns & Jeff Abraham

Johnny Ace. The name doesn’t get much more rock & roll than that, and neither does his story. Even those who aren’t familiar with his music — Memphis R&B from the early 1950s — have heard the name, and most likely the legend attached to it. Paul Simon referenced him in his 1983 song “The Late Great Johnny Ace” (a song in which John F. Kennedy and John Lennon were made honorary “Johnny Aces”). Dave Alvin offered a more straightforward recitation of his early exit in “Johnny Ace Is Dead.” Johnny Ace was one of those tragic legendary rock & roll figures who’s remembered less for the way he played than for the way he left the building.

As legend has it, Johnny Ace went out in a most romantic way on Christmas Day 1954 — romantic like the love scene between Robert De Niro and Christopher Walken in The Deer Hunter. Johnny Ace died at 25, playing Russian Roulette, the game in which you load a bullet into one chamber of a revolver, spin the cylinder, then pull the trigger while pointing the gun at your head. It’s said to be quite a rush if you only hear “click.”

There’s one small catch to the legend of the late great Johnny Ace: It wasn’t Russian Roulette, and it was only a matter of luck that it wasn’t a murder-suicide.

Johnny Ace was born in 1929 as John Marshall Alexander Jr., the son of Baptist preacher. He served time in the Navy and a bit more in a Mississippi prison before he washed up on Memphis’s Beale Street, the bubbling cauldron of southern urban blues, in 1949. He played and toured with Bobby “Blue” Bland and B.B. King in a band called the Beale Streeters before going solo and signing with Duke Records in 1952. There, he was christened Johnny Ace and out of the box went to #1 with “My Song.”

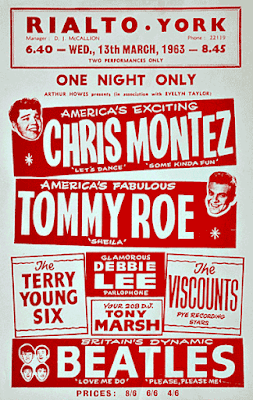

That was the first of eight chart hits in a row, and the beginning of a long slog of touring, much of it with Willie Mae Thornton (also known as “Big Mama” Thornton, enshrined in rock & roll history as the first to record Leiber & Stoller’s “Hound Dog”), a trajectory that blasted him into immortality on Christmas Day, 1954.

Johnny Ace’s last day began the day before. He played a Christmas Eve show in Port Arthur, Texas and drove to Houston for a show on December 25th. At 9 a.m. Christmas morning, he arrived at Olivia Gibbs’ apartment. Olivia was twenty-two years old. She’d attended the University of Wisconsin, but worked as a waitress at the Club Matinee, a blues showcase nicknamed “The Cotton Club of The South.” She was Johnny’s girlfriend. She considered herself his fiancée, and hoped to marry Johnny the following June — if his divorce from his wife and mother of his two kids came through by then.

Olivia later told a reporter that Johnny had invited his band to her place for Christmas dinner. Johnny, she said, wasn’t a doper and he wasn’t a boozer and he wasn’t mean. He was a prankster, always acting foolish, and well, truth be told, he was something of a boozer, after all. Johnny was drinking on Christmas morning, guzzling vodka and playing with his gun. It was the little pistol he carried, a .32 caliber number he’d bought off another musician in Florida. He was always playing with his gun. He liked to shoot at road signs and show off, “just like a little boy,” Olivia said.

When Olivia told Johnny to knock it off and put the weapon away, he did. Then he showed everybody the gold and three-stone diamond ring she’d bought him for Christmas. When it was time for dinner, Johnny Ace used a big knife to carve the Christmas turkey. He was in the Christmas spirit.

“I loved Johnny and he loved me,” Olivia said.

That evening, a crowd of 3,500 showed up for the “Negro Christmas Dance” at the City Auditorium. Johnny Ace was a featured act on a bill that included Big Mama Thornton, Johnny Otis and the headliner, B.B. King. Johnny capped off the first half of the show as usual, by inviting Big Mama onstage and then driving the crowd wild with a duet on his rollicking, rocking hit “Yes, Baby.”

Hey-ay-ay, tell me, baby!

Yay-hey, tell me, baby,

What is wrong with you?

Intermission began around 11 p.m. Johnny was still pranking around in the dressing room backstage at the City Auditorium, drinking vodka, but not in as fine spirits as he’d been earlier in the day. Now he was grousing about a toothache that was killing him. Despite the fact that thousands of fans were in the auditorium waiting for the second half of the show, he said he didn’t think he could go on.

There were four other people in and out of the room. Olivia Gibbs was there, along with her friend Mary Carter. So was another singer named Joe Hammond and Big Mama Thornton. Olivia crawled up onto Johnny’s lap to try to make him feel better. All the while, Johnny Ace was playing with his little .32 caliber pistol, pointing it at people in the room and pulling the trigger. With no bullet in the firing chamber, every time he pulled the trigger, the gun made a snapping sound. Snap! Snap! He was really getting on people’s nerves.

Willie Mae Thornton

Big Mama Thornton, all six feet of her, finally had enough. “Hey, man! What the heck you doin’ with that gun? Don’t you know it might go off?”

“It ain’t got but one bullet in it,” Johnny replied.

“Hell, it don’t take but one bullet to kill you!” Big Mama snatched the pistol, turned the chamber and a bullet tumbled into her hand. She took a swig of 100 proof Old Granddad and headed out toward her second set.

“Gimme the gun!” Johnny demanded as she neared the door. She handed it over.

“You ain’t gonna play with it no more, is you?”

“Where’s the bullet?” She threw it at him.

Snap! Now Johnny pointed the gun at Joe Hammond.

Snap! Snap!

Now he’d gotten on Joe Hammond’s last nerve. “Damn!” Joe spat. “You snapped it at everyone else! Try it on yourself!”

“Now watch me,” said the prankster. “Show you it won’t shoot.” Johnny Ace had his arm around Olivia. He placed the gun to his temple. He pulled the trigger once more.

‘Crack!’ Johnny Ace fell to the floor.

Big Mama stopped dead in her tracks. She swore that when the gun went off, “that kinky hair of his shot straight out.”

“I thought he was just up to his usual playing until I raised his head and saw the blood,” Olivia recalled.

Olivia Gibbs was lucky that Johnny Ace was playing with a small-caliber revolver and that the bullet didn’t pass all the way through his brain. When he pulled the trigger, he was hugging her close. Her head was pressed right up against his.

None of the thousands of dancers in the auditorium heard the gunshot, because Johnny Otis and his band were onstage, playing at the time. They were in the middle of a number when Big Mama came running onto the stage in tears and grabbed the microphone. “The concert is canceled! Johnny Ace has just been killed! There ain’t gonna be no music tonight! Johnny Ace has been killed!”

The Associated Press story was carried in newspapers around the country the following day: “A Memphis, Tenn. bandleader was shot to death playing Russian Roulette last night…

“According to the detectives, Alexander would spin the cylinder, put the gun to the head of one of his companions and pull the trigger. Each time, the bullet failed to come into the chamber. The last time Alexander tried it, however, he sat down and pulled the girl on his lap and put the gun to his head after spinning the cylinder, police said. When he pulled the trigger, the hammer clicked on the bullet, which went smashing into his head.”

The report was not accurate, but the story stuck.

Meanwhile, they carried Johnny Ace’s body back to Memphis. The Reverend Dwight “Gatemouth” Moore, a former blues singer himself, preached over the casket.

Duke Records, Johnny Ace’s label, didn’t waste time crying once word of the tragedy got back to Memphis. Johnny’s next single was released within days of his death, before the new year. “Pledging My Love” was produced by Johnny Otis and featured the Otis band. The opening lines were, “Forever my darling, my love will be true, always and forever, I’ll love just you.” The record became Johnny Ace’s biggest hit, balanced at the top of the Billboard R&B charts for ten weeks beginning February 12, 1955.

The magazine stated that the death of Johnny Ace “created one of the biggest demands for a record that has occurred since the death of Hank Williams just over two years ago.”

Olivia Gibbs, the girlfriend who just missed joining Johnny Ace on his final journey, said the song had been dedicated to her. “I’ll miss those nightly phone calls,” she said. “He called me every night when he was on the road, as if he wanted to hear me for inspiration before he went on the stage.”

###

BURT KEARNS wrote the book TABLOID BABY and produces nonfiction television and documentary films. JEFF ABRAHAM is a comedy historian and public relations executive who has represented comedians from George Carlin to Andrew Dice Clay. The two of them wrote a book about performers who died on stage. It will be published in 2019.