OF DANNY RAPP:

THE FRONT MAN

FOR DANNY & THE JUNIORS

Danny Rapp, the man who first sang “Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay” and “At The Hop” stumbled and fell after stardom faded

July 24, 2018

by Burt Kearns & Jeff Abraham

The Juvenairs were four teenagers from southwest Philadelphia who got together in 1955 to make music. They’d meet on the corner of 54th and Pentridge streets and harmonize, singing doo-wop under the streetlight. Dave White Tricker, Joey Terranova and Frank Maffei were pals at John Bartram High. Danny Rapp, who sang lead, was still a student at Shaw Junior High.

A little guy from a big Irish-American family, Danny was smaller and younger, but he was the leader. He’s the one who made the guys practice, and came up with some choreography and routines that would turn them into an act. Thanks to Danny, they got good. The Juvenairs performed at school parties and sock hops and made a name for themselves around Philly — and that was a good place to make a name, because Philadelphia was a center of the rock & roll industry.

In 1957, a local producer named John Madera got involved. He and Dave White (Dave dropped the “Tricker”) wrote a song called “Do The Bop” and then he arranged for the group to record it. The record got into the hands of Dick Clark, who was not only the city’s most powerful deejay, but hosted an afternoon dance show on television called Bandstand. Dick Clark liked what he heard. He suggested they change the song’s title to “At The Hop” and change the band’s name to Danny & The Juniors. They did.

Danny & The Juniors recorded “At The Hop” and it became a local hit. That same summer, Dick Clark’s television show was picked up by ABC and went national as American Bandstand. After Clark invited Danny & The Juniors onto the show in December, “At The Hop” took off nationally and sold millions of copies.

Danny Rapp was all of 16 years old.

Well, you can swing it you can groove it

You can really start to move it at the hop

Where the jockey is the smoothest

And the music is the coolest at the hop

All the cats and chicks can get their kicks at the hop

Let’s go

Danny & The Juniors, with their white bucks and sweaters, looked like their audience. They were approachable teen idols, and only got more popular after they released their follow-up single a few months later. This song was a genuine teen anthem, a manifesto, a confident yet confused call to arms. Before “My Generation,” “I’m Eighteen” or “Rockaway Beach” was “Rock & Roll Is Here To Stay.”

Rock ‘n roll is here to stay,

It will never die

It was meant to be that way,

Though I don’t know why

I don’t care what people say,

Rock ‘n roll is here to stay.

Of course, the boys didn’t see money from the records. Teenage stardom in 1958 meant television appearances, spots in a few exploitation flicks like the Julius LaRosa movie Let’s Rock, and life on the road. The Juniors hooked up with Alan Freed’s travelling rock ‘n’ roll show, riding a bus with fifteen other acts and getting out to play theatres, nightclubs and halls around the country. The headliner at each stop depended on whose record was where on the charts.

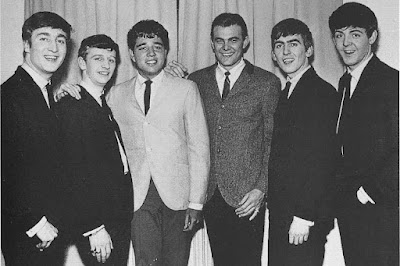

Danny & The Juniors recording 1958

Danny & The Juniors’ record company kept churning out the singles. They charted with a few, even hitched a ride on the Twist train, but never again reached the Top 20. In 1962, Dave White quit the group and moved west. He and John Madera wrote more hits for other people, like “You Don’t Own Me” for Lesley Gore and Len Barry’s “1-2-3.”

Danny & The Juniors soldiered on as a trio, and when the American teen idol rock & roll scene was destroyed by Beatlemania in 1964, went their separate ways for a while. They stayed close to Philadelphia. They took a shot at civilian life. Danny had a wife and kids. He got a job as assistant manager in a toy factory. For a while, he drove a cab.

Then, in 1969, in the middle of Vietnam War protests, drug culture and the Nixon administration, something called the “Oldies format” caught on at a radio station in New York City, and spread through the country. All of a sudden, the old groups from the Fifties were getting back together or reforming around whoever was still alive, and starring in rock & roll revival shows. Fifteen or more acts who’d had hits at least fifteen years earlier were trotted out the way they were on the old Alan Freed tours. Danny & The Juniors came along with their two hits. They hired Bill Carlucci to make it a foursome again, dusted off those stage moves and were back on the road.

I was 16 when I saw Danny & The Juniors perform at one of those shows. It was Saturday night, January 20, 1973 at the New Haven Veterans Memorial Coliseum. They were squished in the middle of a bill that included Ben E. King and a version of The Drifters, The Five Satins, The Ronettes and Jay & The Americans. The emcee (and the reason I bought a ticket) was Don Imus, then the hottest thing in radio.

Danny & The Juniors did their two or three songs, opening strong with “Rock & Roll Is Here To Stay,” closing with “At The Hop.” To me, all of the acts except for Imus were from a different era. I was a toddler when Danny Rapp was in the Top 20. I was looking forward to Thursday, when Neil Young would be playing the Coliseum.

Danny Rapp at 31 had bigger things to look forward to. Somebody had the bright idea of filming some of the big oldies shows and turning it into a movie. Let The Good Times Roll was released in May 1973. Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Fats Domino were the stars, but Danny & The Juniors were squished in the middle somewhere and that was good enough. The movie was a hit that summer, and in August came American Graffiti, George Lucas’s movie about teenagers, cruising and rock & roll in 1962, with a soundtrack filled with oldies.

American Graffiti was a boost but still a kick in the nuts to Danny Rapp and the Juniors. They didn’t make the soundtrack or the movie, but “At The Hop” made it to both. The song was performed in a sock hop scene by the retro rock 'n' roll band, Flash Cadillac & The Continental Kids. Kim Fowley produced the track, which was also released as a single. Flash Cadillac’s “At The Hop” didn’t intrude on the Billboard charts. Neither did Danny & The Juniors when they re-recorded the song that same year.

Nevertheless, the Seventies was the decade to cash in on rock & roll nostalgia. There was Happy Days, Laverne & Shirley, Grease the musical and then Grease the movie (on that soundtrack, “Rock & Roll Is Here To Stay” was performed by Sha Na Na). Danny & The Juniors stayed on the road, playing lounges, hotels — class joints. Only now they weren’t fresh-faced kids in sharp suits. They were men heading to middle age, with lacquered, sprayed comb-overs and matching polyester outfits with big collars. Danny Rapp didn’t dig it. His marriage busted up and it ate at him. His fear of flying got worse. After the shows, spent, he turned off the charm. He kept to himself, he and a bottle. He wasn’t fun to be around.

So what was the breaking point? The twentieth anniversary of singing the same two songs? Looking through the windshield at another endless highway and seeing only more of the same Holiday Inns, afternoons waking up hungover next to the same middle-aged female fans? Near the end of the decade, maybe it was Danny & The Juniors’ latest and strangest trip: another package tour, traveling by bus with another collection of acts. Only this time it wasn’t rock & roll.

It was vaudeville.

In 1978, Danny & The Juniors were booked into another version of Roy Radin’s Vaudeville Revue. Radin had hit on the vaudeville idea during the Summer of Love, back when he was a teenage publicist for the Clyde Beatty Circus. He saw how they raked in big bucks touring backwater towns with old clowns and tired elephants, so he copied the model. Radin assembled a troupe of jugglers, magicians, dancers and ventriloquists, convinced old comedian Georgie Jessel to headline, and sent them out in a bus. It worked.

Roy Radin’s Vaudeville Revue rolled through the Seventies, with tours featuring forgotten old stars like Cab Calloway, Gloria DeHaven and Milton Berle, comics like Jackie Vernon and Stanley Myron Handelman, and oldies groups like the Shirelles. On that 1978 tour, Danny & The Juniors would bound onto the stage following a knockout set by Tiny Tim. They’d perform “Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay” and “My Prayer” and close with “At The Hop”. Emcee Frank Fontaine — Crazy Guggenheim from the old Jackie Gleason Show — would usher them off and introduce the star, “Mr. Show Business.” That was the cue for Donald O’Connor to come out and do a soft shoe to “Mr. Bojangles.”

Around this time, twenty years after Danny & The Junior’s season at the top, Roy Radin was heavy into cocaine and intent on becoming a Hollywood movie producer. He and bigtime producer Robert Evans established a production company to make a film about the legendary Harlem venue The Cotton Club. On June 10, 1983, Radin was found dead in a ditch, shot up and blown up with dynamite by hitmen hired by the woman who’d arranged the Evans deal.

When the vaudeville tour ended, Danny & The Juniors blew up, as well. Like a couple of Philly mob bosses, Danny Rapp and Joe Terry had a sit down and divided up the group and the territories. Joe Terry and Frank Maffei got the East Coast. Danny Rapp took the South, Midwest and West. He hired a couple of other guys and called the group Danny & The Juniors. Terry and Maffei hired Maffei’s brother Bobby. They called their group Danny & the Juniors. The two Danny & The Juniors went their separate ways. They did all right. They played the classy clubs. The two outfits did not overlap or collide.

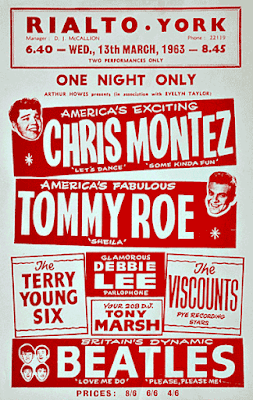

Danny Rapp- The last ad March 9, 1983

There was Danny Rapp, not yet forty, living on the road and dead tired of it, driving by car from town to town with his little band, playing nightclubs and hotel lounges. He’d made decent money all those years, but he never invested or saved any. He could not see an end to the grind.

Twenty-five years after his summer at the top of the charts, Danny Rapp was behind the wheel, on the road with his latest version of The Juniors: a four-piece band, a singer who called himself Bobby C, and another singer, a young woman.

On March 7, 1983, the group opened a month-long engagement in the brand-new Pointe Tapatio Resort overlooking Phoenix, Arizona. The place was so new they were still finishing off the last of the five hundred rooms. Danny and his band were following a successful four-week run by a version of The Platters (that contained no original members!) in the Silver Lining Lounge of the Different Pointe of View Restaurant. Danny & The Juniors were advertised as “light-hearted nostalgic entertainment,” two shows a night, excluding Sundays. Danny would pull down about a grand a week, with a free room and half-price food and drinks, but he was feeling anything but light-hearted and nostalgic.

You couldn’t tell when he was performing. Onstage, Danny was a pro. After twenty-five years, he could do it on his head. Offstage, he was all too often off his head, buying too many of those half-price drinks in an attempt to erase a mistake he made by hiring his latest girl singer a few months earlier. The mistake was having sex with her. Lonely Danny fell hard for her. It was a real romance for a while, but now she wanted to keep things businesslike. Danny would see her after the show, flirting with the yokels in the bar, and it made him crazy. He drank more and his mood got darker. A couple of times, when some hick made a move on her, Danny staggered over, all five-foot-five of him, and things got ugly. Hotel security had to step in to break it up.

Fighting with the hotel guests didn’t sit well with the owners of this classy joint. The last week of the engagement, the girl singer told them that Danny had threatened her. She said she was afraid of him. With three shows to go, she stuffed all her things in a suitcase and flew the coop.

The resort’s vice president scheduled a meeting with Danny at 4:30 the following afternoon, Friday, April 1st. Ken Nagel also had booking agent Charlie Johnston in his office when he read Danny the riot act. Johnston wasn’t happy. He’d booked Danny & Juniors to play Pittsburgh the following week.

“We wanted to make sure we had a quiet ending of an engagement that wasn’t so quiet during the four weeks,” Johnston said.

Nagel recalled that although Danny had been drinking before the incidents in question, he seemed completely sober when he showed up in his office. Yet it wasn’t as if he was paying attention. “I had to repeat things three, four times. It was as if he never quite understood,” Nagel said.

“He was completely out of it,” Johnston said. “Ken was reading the security reports and Danny just said, ‘That wasn’t me.'”

“He kept saying he was not responsible,” Nagel said. “I said, ’Danny, if you’re not responsible for your behavior, who is?’”

Danny responded by changing the subject. He asked for a pay advance so he could get his truck fixed. Nagel gave it to him. April Fools. Now it was Danny’s turn to fly the coop. He packed his bags and drove away. He did not return to the Silver Lining Lounge.

What was left of the band, four musicians and singer Bobby C, performed that night and the next, without their star. “The show is built around him,” Bobby C said. “We pulled it off, but it wasn’t the same show.”

On Saturday, April 2nd, Danny Rapp wound up in the middle of the desert, about 140 miles from Pointe Tapatio. In the tiny town of Quartzsite, Arizona, he checked into one of the mobile homes that make up the Yacht Club Motel. According to La Paz County sheriff Ray Evans, he bought a .25 caliber automatic weapon that day or the next. He was seen drinking heavily at The Jigsaw, one of the town’s two bars.

On the afternoon of Monday, April 4, a maid at the Yacht Club Motel found Danny Rapp dead of a gunshot to the right side of his head. At least the cops were pretty sure it was Danny Rapp. They couldn’t make a positive identification at first because the corpse’s face was blown off. The sheriff said the shot was self-inflicted. He said bottles of booze and some money were found in the room, but no drugs. There was no suicide note, either, but there were notes on several calendars. The sheriff would not reveal the contents.

“It never dawned on me that he would kill himself,” Nagel said after Danny Rapp’s death was official. “He had been having quite a bit of trouble, personal problems, and we wanted to talk to him. He just wasn’t acting like a mature adult.”

“It’s really too bad,” added Johnston, the booking agent. “To think he had reached the pinnacle of stardom in the 1950s and ends up in a little motel in Quartzsite, Arizona. He obviously was really despondent. I don’t know over what.”

Danny Rapp was 42.

They shipped his body the 2,300 miles back home to Philadelphia. About three dozen people showed up for his funeral at St. Agnes Roman Catholic Church. Danny Rapp was buried in New Saint Mary’s Cemetery in Bellmawr, New Jersey, about ten miles from where he grew up.

When Joe Terry was asked about his former bandmate, he wasn’t very nostalgic. “Danny was an alcoholic,” he said. “He had some problems… He had trouble getting a grip.”

Thirty-five years after Danny Rapp shot himself in the head, sixty years since “At The Hop” went to Number One, Joe Terry and the Maffei brothers are still out there, performing as “Danny & The Juniors featuring Joe Terry.” They’re available for corporate and outdoor events, concerts, and shows in casinos and clubs. DannyndtheJuniors.com

###

BURT KEARNS wrote the book TABLOID BABY and produces nonfiction television and documentary films. JEFF ABRAHAM is a comedy historian and public relations executive who has represented comedians from George Carlin to Andrew Dice Clay. The two of them wrote a book about performers who died on stage. It will be published in 2019.