FRED WILLARD WAS

FOREVER YOUNG:

AND REALLY REALLY OLD

Burt Kearns

May 27, 2020

For 60 years, Fred Willard made us laugh playing the same character, from early comedy club gigs with Vic Greco and appearances on Steve Allen’s and Ed Sullivan’s shows to countless appearances on David Letterman’s and Jimmy Kimmel’s shows. And then there were the Christopher Guest films, Spinal Tap, Waiting for Guffman and Best in Show (“he went after her like she was made of ham”). The character he played had a lot of Fred Willard in it—innocence, confidence, decency, naivete. Everybody loved Fred Willard. Burt Kearns spoke to a number of comedy experts about him and shed light on the mystery of his greatness.

“The secret to Fred Willard was his wife, Mary. She was really in charge of his career. She was his protector. They got married in 1968, so it was fifty years. She died two years ago and that was to my mind, sort of the end of Fred Willard in a way. Like, when you’re with somebody for fifty years and then they die and they’re controlling your career, I think he was a little bit lost without her. He slowed down considerably as soon as that happened. Not just career-wise, but physically. You would see him in person, he looked really tired. He would do shows for Dana Gould. They would do live stage readings of Plan 9 From Outer Space and it would be like Dana and Patton (Oswalt) and Fred Willard. And if you saw him before he went on stage or after he went on stage, you could barely talk to him. He was like, winded, and just frail. But onstage, he was back to being Fred Willard.”

That’s Kliph Nesteroff talking. Kliph is a comedy historian – make that the comedy historian (as he will demonstrate). He wrote the essential and definitive book on the subject, The Comedians: Drunks, Thieves, Scoundrels, and the History of American Comedy. He knew Fred Willard.

Then again, everybody in the industry knew Fred Willard, or worked with Fred Willard, or met Fred Willard. I met Fred Willard more than once. A few years ago, I walked into one of those Hollywood autograph conventions, where they were pulling in old stars for me to interview, cold, for a documentary, and who’s sitting there but Fred Willard. We talked a bit about baseball and then he told me that one of his favorite television memories was an interview he did when he starred on an old NBC show called Real People.

“We had a guy called Spaceship Frank who built a spaceship in his garage, and he was going to fly it to Venus and back. And he was deadly serious. I crawled inside the machine and there were no chairs. Frank said, ‘Well, it won’t take that long, it would take a couple of hours. People wanna sit down, we put down some folding chairs in there.’”

Fred loved that one. Where he pulled Spaceship Frank from, I don’t know. It was the one bite we used in the documentary, because it was pure Fred Willard. Fred Willard was the guy on a folding chair in a spaceship on a two-hour trip to Venus. Fred Willard, the comic and improv actor, was brilliant. He was everywhere.

When word spread that he’d died on May 15, the second most striking part of the news, to me, was his age. Fred Willard was eighty-six years old. Eighty-six! Forty months from ninety. How could that be? Fred Willard really was everywhere, always working, and he never came off as an old person, especially not a widower who’d recently lost his wife of fifty years. He was childlike, innocent, and every age group today could claim him as their own.

Fred Willard was the guy on a folding chair in a

spaceship on a two-hour trip to Venus. Fred

Willard, the comic and improv actor, was brilliant.

He was everywhere.

If you’re in your early twenties, you might know him from Modern Family or the movie Anchorman, or if you stay up late, his appearances, up until only a few weeks ago, on Jimmy Kimmel’s show. A little older? It might be Everybody Loves Raymond and all those Christopher Guest movies, especially Best in Show, and maybe all the bits he did on Jay Leno’s Tonight Show. Get a little greyer and it’s Roseanne, and dozens of appearances on Late Night with David Letterman in the 1980s. Old like me and it’s Fred Willard in This Is Spinal Tap, and as Jerry Hubbard, second banana to Martin Mull’s Barth Gimble on the fake television talk show, Fernwood 2 Night.

What’s wild is that Fred Willard was doing it much longer than that, in a career that goes much farther back, all the way to those black-and-white Lenny Bruce-Mort Sahl coffeehouse days. What’s wilder is that Fred had all these generations laughing, playing the exact same character.

Fred Willard by Burt Kearns

Hip Guy Playing A Square

“He got into show business, 1958, ’59.” Kliph tells me how Fred Willard, after a hitch in the U.S. Army, arrived in New York City from Shaker Heights, Ohio and enrolled at a place called “The Gag Writers Institute.”

“It was one of these charlatans who wasn’t funny at all who was teaching the class on how to be funny. Fred enrolled in that. The other members of the class included Ron Carey from Barney Miller and Vaughn Meader, who did the JFK impression. They were all in this class together. And that’s where Fred met this guy, Vic Greco. They were workshopping with sketches in this class and were supposed to do a showcase at the end of the course. And the teacher said, ‘We’re just gonna have you two do the whole showcase,’ because Fred and this guy Greco were standout funny. I think the showcase was called An Evening with Fred Willard and Vic Greco. Everybody else was pushed to the margins, playing incidental characters in their showcase.

Fred Willard’s comedy doesn’t work as well

if the person in the audience is the same type

of person as the character he’s playing.

“After they finished that course, they took those sketches they did in the class on the coffeehouse circuit, performing a nightclub act as Willard and Greco. They played the Phase 2 and the Gaslight in Greenwich Village in 1960, ’61, ’62.

“I haven’t been able to verify this, but the advertisement for it seems to indicate that they recorded the laughter, the audience reaction. They didn’t record the show. They put microphones in the audience for the laughter to sell it to television networks to use as a laugh track. I don’t know if it ever actually ended up being used or not, but I think they thought that original Fred Willard performance would get some really big laughs from the audience, so they recorded the laughs to use in canned laughter. I think maybe this is how the guy from the Gag Writers Institute sustained himself financially.”

Television followed. “Steve Allen was the first person who, quote unquote, ‘got’ him,” Kliph says. “Like, he got it. Fred Willard’s comedy doesn’t work as well if the person in the audience is the same type of person as the character he’s playing. You know what I mean? Like a naïve, sort of, dolt. Somebody might see Best in Show and just not get the joke. Fred Willard for his era was very hip. This hip guy playing a square. And so, hip people got it and squares maybe missed it, especially in that era when comedy had to be more on the nose, more spelled out. It wasn’t as subtle.

“Steve Allen, though, got that subtlety right away. He became a big booster, and said Willard and Greco were the lineal descendants to the Marx Brothers. He used them a bunch on his various shows and was always the best audience, with that big cackling laugh that you could hear offstage.”

Willard and Greco played The Ed Sullivan Show four times. They were guests on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in its first year. They did the The Merv Griffin Show. “They did a ton of TV shows in the ’60s,” the comedy historian says. “They did The Dean Martin Show, they did The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. They did an episode of Get Smart. It was supposed to be the pilot for their own series, but Fred’s manager fucked it up when he held up Leonard Stern and Talent Associates for more money for their own series. They never got to do it.

Steve Allen, though, got that subtlety right away.

He became a big booster, and said Willard and

Greco were the lineal descendants to the Marx Brothers.

“And at one point, they were supposed to be hired as the company of players on the original 1968 Carol Burnett Show. Instead of Harvey Korman and Tim Conway, they were going to have Fred Willard and Vic Greco. And again, the manager held them up for more money and they never got to do it. Fred was really pissed off about it. And, in fact, maybe it wasn’t even their manager. It may have been his partner, Vic Greco. I think that soured the relationship and that’s why they broke up.

“They broke up and then they got back together. They broke up the first time because Fred joined The Second City in Chicago in 1965. The other notable players in that cast that year at Second City were Robert Klein and David Steinberg. And right away, Robert Klein said it was obvious that Fred ‘had it.’ He was this unique comic voice with his own special rhythm that nobody else could steal. He was unplagiarizable.”

Hip People Got It

That comic voice? “Pretty much he was always this kind of clueless guy, this guy who was confident but stupid,” Kliph explains. “You can’t really compare it to anything else, it was so unique. If you were to compare it to anything, you could compare it to Bob and Ray. In the early ’50s, they did the same thing. They played sort of, stupid, naïve, folksy people who did not realize that they were ridiculous. And it kind of attracted the same sort of audience as Fred Willard. Hip people got it. But people that were too close in tone to the characters that were being portrayed or parodied didn’t understand that it was comedy. So it’s hard to define what it is. But very, very few people could do that.”

A lot of words get thrown around when describing the comic voice that carried Fred Willard for sixty years. Dunderhead. Dimwit. Clueless. Genial buffoon. “Everyone thinks of Fred Willard as a brilliant comedian, but I think we really should say, ‘Fred Willard was a brilliant actor,’ because he really acted like an idiot in those roles, and you really believed he was that dumb guy.” That’s Jeff Abraham talking. My co-author on the book The Show Won’t Go On, Jeff is the publicist for and board member of the National Comedy Center and owner of the famed Abraham Comedy Archives. He knew and worked with Fred. Of course he did. “There’s that expression, ‘You’re acting like a kid, you’re acting like a clown,’ and that was Fred,” Jeff says. “He was so brilliantly acting, you almost believed he was that character. He almost had an angelic quality in all those Christopher Guest roles. He really became the dog show commentator. He really became that person. And I think that came from all his years of improv training.

Everyone thinks of Fred Willard as a

brilliant comedian, but I think we really should say,

‘Fred Willard was a brilliant actor,’ because

he really acted like an idiot in those roles,

and you really believed he was that dumb guy.

“He definitely had an innocence. There was a childlike innocence about him, but we should not be completely fooled. He was not completely innocent.”

‘Do Not Open Zipper and Pant’

No, Fred Willard wasn’t completely innocent, but it was the innocent quality he brought to his characters and exhibited in real life, that carried him through an unfortunate and uncharacteristic scandal eight years ago. Fred was arrested and charged with suspicion of lewd conduct at the Tiki Xymposium Adult Theater, a raunchy, sticky shack on a seedy stretch of Santa Monica Boulevard in Hollywood. A jerkatorium with a sign over the turnstile that read “DO NOT OPEN ZIPPER AND PANT.” When that news broke, the shock for me and most other people wasn’t that he was accused of whacking it in a porno house, but ‘Fred Willard is seventy-eight?’ Everybody gave him a break.

“Not only was he eventually cleared, rather than have his publicist put a spin on it, Fred kind of made a joke of it,” Jeff recalls. “He wound up critiquing the movie and making fun of the theater itself. Fred was not a swashbuckling playboy, you know? ‘What are you doing in the theatre? You could get all the women you want!’ He was kind of an everyman, so it was like an innocent mistake. And nobody really cared enough to dig into his background to see if he was going to the theater for the last thirty years or was it one time. They gave him a pass!”

He definitely had an innocence. There was a

childlike innocence about him, but we should

not be completely fooled. He was not completely

innocent.

After the arrest was announced, comedian Albert Brooks summed up Hollywood’s shrug with a tweet: “I love Fred Willard. He’s a great guy. For his birthday I’m getting him a den and a home computer.”

I read the Brooks tweet to my pal A.J. Benza, the former New York Daily News gossip columnist and host of the old Mysteries & Scandals cable series. Nobody mentioned Fred’s porno house arrest in the days following his death — nobody but A.J. He talked about it in detail on Fame Is A Bitch, his hardboiled podcast that mixes news, gossip and Hollywood history. Of course, A.J. had been to the Tiki Theater. Doing research.

“That’s great. That’s funny,” A.J. says when he hears the Brooks tweet. “Well, he also got busted in 1990. They don’t talk about that that much. So he definitely had a kink, like he liked to do that. I actually said that on my show. ‘Maybe he had a wife who didn’t want him to look at porn, I don’t know.’ But for Christ’s sake, now it’s free everywhere. Was it free in 2012? I can’t remember if it was.”

A.J. gave Fred a pass, and so did the gossip media in 2012, who laid off the guy because of Fred’s persona – “It was ‘Fred, he’s harmless. Let him do what he’s gonna do.’ Yeah, yeah, yeah.” — but also because he was one of those entertainment figures who was above the gossip culture, in A.J.’s words, “Too hip for the room. And I don’t think everybody got the joke sometimes. Some guys are too hip for the room, and I think he was so good at playing that (part), that he was just too hip for the room for a lot of people. So he just doesn’t fit in.”

Then A.J. changes the subject. “But what a terrific guy, man. Did you watch Fernwood 2 Night? You must’ve saw that when you were younger. He’s just one of those guys that’s a treasure!”

And here’s the punchline. A.J. Benza is also an actor (he’s in Gravesend, the new mob series on Amazon). When he arrived in Hollywood in the late 1990s, the first movie role he landed was in a picture called Chump Change. His first scene was opposite Fred Willard.

“The movie was directed by a guy named Steve Burrows. The movie’s about a guy writing a script who comes to Hollywood. At first, everybody loves the script, and then they want changes, so the guy’s making all these changes. I was his agent and Fred was his manager. And of all things, Jerry Stiller played the studio head. Talk about a movie. I read the script. One of those independent movies that made me laugh like crazy. I couldn’t wait to do it. Then I find out Fred Willard is playing the manager, and I was so excited.

“Fred and I worked a day and a half together. So we do the script the way the guy wrote it. Very funny. And then Fred takes Steve aside and says, ‘That was great. Uh, do you mind if I just do a couple of wild lines? Do it my way? Can I give it a shot?’ And Steve’s like, ‘Of course. Are you kidding me? Have a ball.’ And then Fred does all the things he thinks he should say, and every one of Fred’s lines stayed in the movie. The kid was like, ‘Forget about my writing. This is gold!’ He’s perfect. He just gets it immediately.

“The day we worked, there was nothing about him to suggest, ‘I work with the biggest stars, I’ve been in these movies and this TV show.’ He just comes on the set, and he didn’t want anybody to treat him differently. Very matter of fact, very kind. He didn’t have any airs about him. So that made me even go more crazy, because I couldn’t believe I was gonna be on a movie with him and act next to him. I’m just looking at him in awe, because when I was fifteen, to see Fernwood 2 Night was like, how could I be so lucky that there’s a show with Martin Mull and Fred Willard? Fernwood 2 Night was insanely funny to me.”

There was nothing about him to suggest,

‘I work with the biggest stars, I’ve been in

these movies and this TV show.’ He just comes

on the set, and he didn’t want anybody to

treat him differently. Very matter of fact,

very kind. He didn’t have any airs about him.

Always A Put-On

“Again, Fernwood 2 Night is one of those things where hip people got it and squares were confused,” Kliph Nesteroff says. “They weren’t sure if it was a real talk show or a fake talk show. Now it’s so common to do a fake talk show that it’s almost hack. But Fernwood 2 Night was the first to do that, to kinda trick you into wondering, ‘Is this real or is this fake or is this part real? Is this part fake? Are these actors?’ The guests sometimes were real people and sometimes they were Harry Shearer. So it blurred that line. Norman Lear’s name was attached to it, but he had sort of a standoff approach. And it was syndicated, which gave it this mysterious feel because it aired at different times in different markets. Sometimes late at night, sometimes during the day.

“And Martin Mull was considered a very hip comedian at the time. Martin Mull was sort of like Steve Martin before Steve Martin. Martin Mull heavily influenced Steve Martin. And this was a new era of comedy in the Saturday Night Live era. The SCTV era. The Steve Martin era. The Albert Brooks era. The Fernwood 2 Night era. And what they all had in common is that they all made comedy about comedy. About show business. We kind of take that for granted now, because stand-up comedians go up on stage and they talk about television and SNL‘s famous for its commercial parodies. But before that wave when Albert Brooks was making fun of ventriloquists, people didn’t do that. Nobody going on Ed Sullivan and making fun of the ventriloquist. They would have real ventriloquists. And so this was a first generation of comedians that had been raised with television.”

Martin Mull was sort of like

Steve Martin before Steve Martin.

From This Is Spinal Tap in 1984 to The History of White People in America, and D.C. Follies (“Sort of a ripoff of Spitting Image in the UK, with puppets, but didn’t have the same cutting political satire”), Kliph says Fred Willard “was everywhere in the 1980s.

“He was like a utility comedy player. One of the places before Christopher Guest you would see him most regularly was on Late Night with David Letterman. He must have appeared twenty or thirty times. And he was sort of like Bill Murray or Richard Lewis or Robert Klein. There was a handful of Letterman guests in the ’80’s who, every time they appeared, they did something brand new. In fact, I would compare Fred Willard on Letterman in the ’80’s to Will Farrell on any late-night talk show today. Will Farrell will come out as a character or dressed in a costume. It’s always something different every time. And that’s what Willard did. He would do these very elaborate conceptual pieces, always a put-on.”

That Clueless, Bumbling Voice

“I think it was Michael McKean who I interviewed, who said the thing that he loved about Fred Willard was when everyone would make a right he would go left.” Danny Wolf is talking now. “He always kept other actors very sharp. He said, ‘Fred Willard was the only actor you could never keep up with. Because when we all go right, Fred’ll go left, and you gotta be on your toes.’ He was so quick. And if you see anything from Best in Show to Waiting for Guffman, I don’t want to say he steals the movies, but for Best in Show he certainly should’ve been nominated for a supporting actor Oscar. Best in Show is what I interviewed him about.”

I’ve known Danny Wolf since he was a producer on that first wave of television network “clip shows,” like Busted On The Job, that featured videos of chefs peeing in the soup or mailmen getting attacked by pit bulls. Danny directed the new, three-part documentary series, Time Warp: The Greatest Cult Films of All Time. Two parts have been released. The third, dedicated to comedy, is available to stream on June 16. Danny interviewed Fred Willard for that one.

“I picked Best in Show as one of the great cult films of all time, partly because of Fred, because something that makes a cult film is a movie that’s quotable and lines you never forget. And most of the funniest and quotable lines in Best in Show are Fred Willard’s.

I ask him, “And these were improvised lines, right?”

“Yeah,” Danny says. “People kind of know, with (director) Christopher Guest, you get an outline and he sort of lets you go. I think Fred did everything in a day or day and a half. All his lines. And that just goes to show you what a talent he is, where there’s that much good ad libbing. To have the ability to do that without a script, and that can roll off your tongue and come out of your mind just shows what a genius the guy was. People do use the word ‘genius’ very flippantly here. The word ‘genius,’ gets bantered and thrown at people like it’s nothing anymore. Very few people really earn or deserve genius. He did.

“We sat in Fred’s living room, and the coolest thing is he went into his Buck Laughlin character when I was interviewing him,” Danny says with real excitement. “He actually opened the interview with, ‘We’re here at the Mayflower Dog Show!’ in that voice. He based that on Joe Garagiola (the baseball catcher turned television announcer and host), which he talks about in my documentary. And I just got the chills. It’s like, Oh my God, he’s doing, ‘Hey, you went after her like she’s made out of ham!’ And he did it in that kind of clueless, bumbling voice of his. And you just go, ‘Man, that’s awesome.’ It’s Fred Willard doing Buck Laughlin in the interview, and I got the chills.

The word ‘genius,’ gets bantered and thrown

at people like it’s nothing anymore. Very few

people really earn or deserve genius. He did.

“It was a thrill,” Danny says, reliving it. “I mean, to sit across — you know, I did interviews with a hundred and fifteen celebrities over those couple of years, and met everyone from Jeff Bridges to Jeff Goldblum to John Turturro to Tobe Hooper. And sitting across from Fred Willard probably gave me more chills than any of those people I just named because not only did I grow up with him, but he’s just the kind of guy you like and you want to like and you know he’s nice, and you know he’s gracious. He made us feel at home immediately and made the interview very easy for me because of how relaxed he is and how funny he is and how cool he is.

“You know, it’s not like Gary Busey, when you ask a question and there’s sort of this intimidating, ‘How is he gonna answer it? Is he gonna be an asshole? Or will he even answer the question straight?’ Every question you asked Fred, you know you’re gonna get a great answer. You know it’s gonna be funny. You know it’s gonna be honest. And it just made me like him even more than I liked him going in. And that was hard, because I already loved him going in. And I loved him even more when I left.”

“I know you,” I tell Danny. “And I know you actually did get chills from him, knowing you.”

“Yes, I did.”

Tom Jones’ Opening Act

Back to Kliph Nesteroff: “He had originally been cast in either the Robert Stack or Leslie Nielsen role in Airplane!, and he turned it down because he had just done a string of bombs in movies in ’77 and ’79. He made this movie called Cracking Up with the guys from Firesign Theatre, for Sam Arkoff from American International Pictures. It was a wacky comedy. It was an absolute disaster. And then he did this movie Americathon, which was a wacky comedy. And an absolute disaster. So then he gets the script for Airplane! in ’79 and says, ‘This is the stupidest thing I’ve ever read.’ They wanted him for the lead and he turned it down.

“He was in some weird movies. He was in a trucker movie called Flatbed Annie & Sweetiepie, which starred Annie Potts and Harry Dean Stanton, and Arthur Godfrey, right before he died. He was doing all these B movies. He was in a sexploitation comedy called Chesty Anderson U.S. Navy. And he played a serious role in the first adaptation of a Stephen King novel, Salem’s Lot. Most interestingly, he was in a movie by the French filmmaker Jacques Demy called Model Shop, an art house movie.

Every question you asked Fred, you know

you’re gonna get a great answer. You know

it’s gonna be funny. You know it’s gonna be

honest. And it just made me like him even more

than I liked him going in. And that was hard,

because I already loved him going in.

“He did all kinds of little things here and there, but those things were all tangential from comedy. Comedy was the main thing. And then the Ace Trucking Company. They were a clever sketch troupe, sort of an outgrowth of the style that had been founded by The Committee, which was sort of intellectual sketch comedy. You know, Compass Theater informed The Second City. Second City informed The Committee. They got signed by Tom Jones to do many appearances on his show which was filmed in the UK and they became his opening act. So for a while, Fred Willard was Tom Jones’ opening act.” Kliph laughs. “And Ace Trucking Co did hundreds of TV shows. The Dick Cavett Show and forgotten talk shows like The Barbara McNair Show, The Woody Woodbury Show. In ’69, ’70, ’71.”

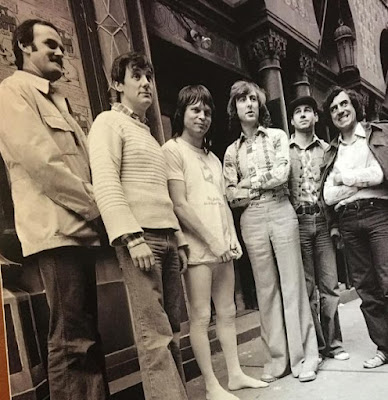

Painting of Fred Willard in his home,

photo by Danny Wolf

When I talked to Fred back at that Hollywood convention, he couldn’t believe that anyone remembered his old work, playing that same “Fred Willard character.” Maybe that was his secret. By not reinventing himself, he was new to every generation. “Most people remember Best In Show, a lot of people remember Fernwood 2 Night, which is before that, which is amazing,” Fred said. “And every once in a while, someone comes up with a really old thing and it’s like, ‘Oh God, where did that come from?’”

‘A Comic Genius On Your Hands’

“He was pretty ageless,” Danny Wolf says. “If you look at him in, say, Waiting for Guffman, and you look at him in Modern Family, and you’re talking maybe a fifteen-year difference in when they came out, and you know what? He didn’t change that much in appearance. And his voice certainly didn’t. He had kind of that distinctive ‘Hey, it’s Fred Willard’ voice. Two weeks before he died, he was doing Kimmel. He just seemed like the kind of guy who would work ’til he died. And he did.”

“His character really was able to age as he went along,” Jeff Abraham tells me. “On Kimmel, he was playing these befuddled senators and politicians. So he could play the father and things and older statesmen as he aged.

“I think the people who were in charge were smart, because they knew how good he was. And they did not let his age get in front of him. So if you were a producer on Raymond, you said, ‘Oh, let’s get Fred Willard. He’s delivered. I grew up with him from Spinal Tap.’ And the people behind Spinal Tap said, ‘Oh, I know him from the previous generation.’ So I think all the smart people knew how good he was and said. ‘Let’s not get a Fred Willard type, let’s get Fred Willard. And so he was finding a new audience every generation. And most performers don’t get that. They have their great run and they kind of disappear.

“I mean, here’s a guy who gave us sixty years of laughter, from when he was in sketches up until work that will come out after he dies (like Danny Wolf’s documentary and the Netflix series, Space Force). Making someone laugh is easier said than done, and then to do it so well and so long is more icing on the cake. So that’s how I want to remember Fred.”

Let’s not get a Fred Willard type,

let’s get Fred Willard.

“He was a sweet, sweet dude,” Kliph Nesteroff says. “Like I say, his wife Mary, who passed away a year and a half ago, she was sort of his bodyguard, his manager, unofficially. She kept a watchful eye to make sure that nobody was trying to take advantage of Fred, because he was so genuinely nice that you could very easily recruit him for some sort of crazy scheme. There was this string of naivete that he played in all of his characters that was also sort of real. He was genuinely nice. If somebody shouted up to him, ‘Hey Fred!’ on the street, he would stop. Most celebrities would put their head down and keep walking. He’d stop and engage with the person and then start to wonder how he knew this person. But he didn’t know them, they were just a fan. So Mary was the one who would come in and say, ‘Okay, move along.’ She was like his protector and his guide, so, when she died, I thought to myself, “Well, I wonder when Fred’s gonna die,” because it’s gonna be sooner rather than later, just because they were so tightly connected. And sure enough.

“Everybody loved using him. He was just a joy to work with. Everybody wanted to work with him because he always delivered. You could always count on laughs. And he never stopped working. That’s so rare that this happens for anybody in comedy, that they transcend generations. Because if you look at anybody who appeared on The Merv Griffin Show or The Steve Allen Show or The Ed Sullivan Show the same year that Fred Willard did, there’s nobody under the age of forty who wants to watch it or will enjoy it for any reason other than maybe camp. Even the biggest comedy fan today who’s downloading podcasts or trying to do stand-up, none of them are watching Norm Crosby. None of them are seeking out Alan King. Not even the younger generation. They’re not interested in Mort Sahl or even Nichols and May.

There was this string of naivete that he played

in all of his characters that was also sort of real.

He was genuinely nice. If somebody shouted up

to him, ‘Hey Fred!’ on the street, he would stop.

Most celebrities would put their head down and

keep walking. He’d stop and engage with the person

and then start to wonder how he knew this person.

But he didn’t know them, they were just a fan.

“But Fred Willard they still responded to, still genuinely belly-laughed at his performances. Even though he’d been around since the early ’60s and was in his eighties, they would still find him truly, truly funny. They didn’t have to qualify it or say it’s funny for his age or funny for his time or it’s funny in its context or anything like that. Even people that are still alive that he worked with, like Robert Klein and his contemporaries from Second City — and this isn’t a put down, but there’s nobody under the age of fifty who’s excited about Robert Klein or David Steinberg. But they are excited about Fred Willard. You could still show Best in Show or any other Fred Willard performance to somebody in their twenties and they’ll respond to it. They’ll find it funny. So that is the rarest thing in comedy, and that’s when you know you have a comic genius on your hands. The only other person I could name like that would be Mel Brooks. And maybe Steve Martin. But that’s about it.”

I let that sink in, and say to Kliph, “Well, that’s the greatest tribute, I think, that you can give to him. And especially, as they say, coming from you, that’s a beautiful tribute to Fred Willard.”

“Yeah, and the thing is you don’t even have to puff it up for an obituary,” Kliph replies. “Like, it’s the truth. What I am saying, I think we could all acknowledge is true. And the fact that he worked so much right up until his death is a testament to that. Never stopped being hilarious to people in their eighties or people who are in their twenties. And that just never happens in comedy, unfortunately. It’s very rare.”