BURT KEARNS

NOVEMBER 7, 2018

He joined the Crickets after Buddy Holly died in a plane crash, befriended Roy Orbison, toured with Dusty Springfield, the Everly Brothers and the Searchers… and then died in exactly the same manner as Buddy Holly

by Burt Kearns and Jeff Abraham

On February 3, 1959, a small plane crashed into a field, killing four people, including the rock ‘n’ roll singer from Lubbock, Texas who, with The Crickets, recorded a song about Peggy Sue. That date was later declared “The Day The Music Died.”

It didn’t, though. The music, that is. It didn’t really die that day. Buddy Holly, former leader of The Crickets, was already a star and innovator, and was immortalized by his premature death. The music of fellow crash victims Ritchie Valens, the teenage Chicano rocker, and songwriter-deejay J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson still plays on, celebrated and imitated sixty years after that fatal trip.

“The Day The Music Died” is a label that might be better applied to the day a small plane crashed into a field, killing four people, including the rock ‘n’ roll singer from Lubbock, Texas who, with The Crickets, recorded a song about Peggy Sue.

That date was October 23, 1964. The musician was David Box. To many, he’s the answer to a trivia question, part of a bizarre Celebrity Babylon coincidence: the guy who replaced Buddy Holly in The Crickets and wound up dying — the exact same way.

A dig, and not even too deep, reveals much more. As it turns out, David Box was a talent on par with Buddy Holly, cut short on the verge of success. Buddy made it to 22. David Box died at 21. His recorded legacy may have remained dead to the world, if not for one woman who’s spent more than fifty years making sure David Box’s music stays alive.

The first people to visit the Boxes were Buddy Holly’s parents….

L.O. Holley said to Mr. Box:

“People would tell you that time heals the pain, but it does not.”

“David’s style was so far ahead. His style was just so clean and so solid,” Rita Box Peek told us.

Rita is David Box’s kid sister. She came along five years after his birth. She was sixteen when he left this world. She’s seventy now.

“He and the way he presented himself musically was just solid, crisp, clean. Other musicians, serious musicians who really are naturally talented and gifted, recognize that. They can hear it — the ears tell the truth. And they can hear who David was and what he was all about. He was a star.”

Terry Allen agreed. The acclaimed outlaw country singer and conceptual artist was David Box’s high school pal. “David was the first person I knew who not only wanted to be a rock ‘n’ roller, but was going to be one,” he said. “He was the first person I met who was totally serious about writing songs, making music, performing and making it his life. In that sense, he was the first real artist… in the true sense of that word… I ever met.”

THE SPARK THAT RESONATED

Harold David Box was born to Virginia and Harold Box in Sulphur Springs in east Texas on August 11, 1943. Daddy was a self-taught Western swing fiddler, and not a bad one at that; good enough that when David was a baby, the family pulled up stakes and drove off toward Las Vegas. Daddy and four members of his band, The Dixie Ramblers, planned to find full-time work playing music in the show town.

They made it clear across the state from Plano before stopping in Lubbock — impressive, but still about 850 miles short of Sin City. They planned to stay on long enough to earn some money for the rest of the trip. They stayed too long. They never left.

Harold “Boxy” Box and his buddies became the Sunshine Trio and performed five days a week on Lubbock’s radio station KFYO. It was good for the soul but not enough to pay the bills. “He had a real job,” Rita said. “And that was really difficult for him, because a musician’s mission is to do music all the time, not have to separate themselves from the joy of all that with the daily grind.”

Young David got the performing bug before he was three. It was a talent show at the Palace Theater on Main Street, broadcast on KSEL. David sang “New Jole Blon” and “If I Had A Nickel.” He won, with three curtain calls and $13 in tips.

He got his first guitar on his ninth birthday. Daddy helped teach him some chords. David took it from there. Rita remembers the time he spent noodling, inventing, coming up with new chords and rhythms. She remembers the calluses on his fingertips, and his pure tenor voice.

David wasn’t even in his teens when one of his Lubbock neighbors started making music, and noise, in town. Charles Hardin Holley, better known as Buddy Holly, and his high school chum Bob Montgomery played country and bluegrass music on the radio and at outdoor venues as Buddy & Bob. By the time David was a teenager, Buddy Holly was playing rock ‘n’ roll for the world.

“Here in Lubbock, Buddy Holly was just like the center of the universe with the young teenagers and David’s generation, and so David went immediately to rock n’ roll,” said Rita. “Buddy Holly was a catalyst that just snapped that spark that resonated in David and so many others.”

DON’T CHA KNOW

David was fifteen when Buddy Holly died in that plane crash. That same year, David got a Stratocaster guitar like Buddy’s and started his own bands: The Rhythm Kings, The Shamrocks, and most notably, The Ravens.

“When he formed The Ravens, that’s part of how Buddy’s life as a very successful musician affected David,” Rita said. “Other kids probably were very much on the same track, except they didn’t have the ability to take it as far as David did.”

“David wasn’t trying to be Buddy Holly at all,” she insisted. “Not at all. He wanted to be as successful as Buddy was musically, and he wanted to be successful businesswise. David took himself very seriously. He took what Buddy had accomplished as his example, but David had his own style developing.

“It’s like an artist whose teacher is somebody like Rembrandt or Van Gogh. You’re naturally going to take on their tendencies and their techniques, but as you’re progressing and practicing, you’re moving along with your own talents. So you have good foundation. ”

By the time of his death, Buddy had left The Crickets behind and was performing as a solo act. Crickets’ drummer Jerry Allison and bassist Joe B. Mauldin left Lubbock for Los Angeles and carried on with Holly’s old friend Sonny Curtis on guitar and lead vocals.

“That is when there’s all kinds of destiny in play,” Rita said. “David’s drummer (Ernie Hall) lived across the street from Jerry Allison. And Jerry’s mother and Ernie’s mother were very close friends. That’s how Jerry found out about David, because David was going over to Ernie’s house and they would practice.

“And David and The Ravens had gone to a little studio — it really wasn’t a recording studio as it was a little spot in Lubbock where commercials were recorded — and they cut a couple of songs. One of them was a song that David wrote, ‘Don’t Cha Know.’ It was a little 45 demo, and when Jerry heard that, it was like, ‘We want to hear more of David singing.'”

HIGH SCHOOL CONFIDENTIAL

As destiny would have it, the following year Sonny Curtis went off to the Army, but The Crickets were contractually obligated to deliver one more single to Coral Records.

“They needed someone, and David fit the bill, and not only that, they were just blown away by his voice at such a young age,” Rita said. “He recorded ‘Don’t Cha Know,’ which was the A side, and then the B side, Buddy Holly’s ‘Peggy Sue Got Married.’ David recorded that on his seventeenth birthday.”

The Crickets 45 featuring the David Box song.

After the recording sessions in Los Angeles, Ernie Hall went home to Lubbock. David Box stayed and toured with The Crickets for a few weeks. His career could have taken a different turn had not those weeks ended in September, and the start of David’s junior year of high school.

Rita said, “By the time Mother and Daddy and I drove from Lubbock to L.A. to pick him up, they offered David a contract to be a Cricket. I was there when David was offered the contract in L.A. I was twelve years old. Daddy knew that he couldn’t read the contract the way a lawyer would be able to read and point out this is not good, or this whole thing stinks. It was just like, ‘Okay, here’s the contract sitting on the kitchen table, sign here. And it’ll be great, don’t worry.’ And our dad looked at the situation and said, ‘No.’ Because David was still a minor. Daddy had a very, very negative feeling about the whole situation. He understood that something wasn’t right. (Note: And something wasn’t right. Crickets Music, Inc., snuck a line into the recording contract that took ownership of David’s song for one dollar.)

“David was not broken up about not being involved anymore,” Rita recalled, firsthand. “He didn’t kick the cow, he didn’t pull hair, it was just like, ‘Well, that’s just the way it is.’ And when we came home, he said, ‘I’m done with bands.’ Well, that ought to tell you something. The fact that he already had the experience with The Crickets was not one of those ‘made in heaven’ kind of things. In fact, he didn’t want anything to do with the band any more after this.

“It’s just that he was a star. And he didn’t act like it, okay? Like BJ Thomas said about David, he was a very unassuming guy, but — and I quote, ‘there was something great there.’ He was very quiet, almost shy. But he wanted to call the shots on his own, one hundred percent. And when you’re in a band, that does not happen. If you’re the lead singer, somebody’s got you on a leash.

“He loved L.A. He was so glad that he had the experience, but he was also glad to be back home. Because the first thing he did when he arrived home, he bought himself the best briefcase that he could possibly buy. And that briefcase became his symbol for the serious business. He took his music seriously, and he took himself seriously.”

David Box went back to school.

“He had no business being in school,” Rita said she always knew. “He should’ve been on stage. I mean, this is not the kind of person that you’d put in a classroom and say, ‘Okay, we’re gonna put you in a little slot here, and you’re gonna do this assignment or that.’ It’s like, ‘No, I’m gonna be over here singing and playing and–‘ It was one of those deals. But he really wanted his high school diploma.”

IF YOU CAN’T SAY SOMETHING NICE

David didn’t give up his musical ambitions. In fact, his father, who steered him away from a career as a Buddy Holly karaoke singer, helped move his career to a new level.

“Our dad knew Ben Hall, a Western swing musician here in Lubbock,” Rita said. “Ben was well known. In fact, Ben wrote ‘Blue Days, Black Nights,’ that Buddy Holly recorded (note: it was Buddy Holly’s first single). Ben had his own independent recording studio in Big Spring, Texas, a little over a hundred miles south of Lubbock. Ben Hall let David record in his studio, for free. David would sing and play and Ben was basically financing the studio time. He was just giving him that, because we did not have the money. Period. You just cannot squeeze money out of a rock.”

David’s work with Ben Hall led to the offer of a songwriting, then a recording contract with a small local label called Joed Records. This time, Daddy signed the contract, which led David to a meeting with Roy Orbison.

“Roy was still living in Odessa,” said Rita. “Odessa’s not that far from Big Spring, and so they all knew the studio. And David and Roy struck up an immediate musician friendship, and friendship beyond that — good buddies and hang out together kind of thing. Here’s David, the fire has been struck with Buddy Holly and now he has Roy Orbison’s influence, not only musically, but in friendship. It was just really, really neat.”

Roy Orbison told people that David Box was the second-greatest guitarist he’d ever heard. Roy, of course, considered himself to be the best. On April 4, 1962, while a senior at Lubbock High School, David Box was in RCA Studio B in Nashville to record two songs Roy Orbison had written with Joe Melson and Ray Rush. Backed by top session musicians including Floyd Kramer, Bob Moore and Hargus “Pig” Robbins, David recorded “I’ve Had My Moments” and “If You Can’t Say Something Nice.”

David Box graduated from Lubbock High School on June 1, 1962. Over the next two years, Joed released “If You Can’t Say Something Nice” and two more David Box singles. Even leasing out the tracks to a label in Los Angeles couldn’t get them to chart. David realized the record business might not pay off. The clean-cut kid with the briefcase also had a talent for drawing. He enrolled in a correspondence course with The School of American Art in Westport, Connecticut.

DEATH TAKES A PLANE RIDE

David returned to Nashville in 1963, did session work, learned about producing and toured the East Coast with Orbison, Dusty Springfield, The Everly Brothers, Bobby Vee, and The Searchers (the British invaders included a version of David’s “Don’t Cha Know” on their second album). Back home, he began playing gigs with Houston’s top rock ‘n’ roll band, Buddy Grove & The Kings.

In August 1964, when he turned twenty-one, David got out of his contract with the small town record label. Buddy Holly’s former business manager Ray Rush helped him get signed to a major record label — as major as one could get: Elvis’ label, RCA Victor.

That same month, the five-piece Kings backed David Box at KILT Radio’s Back-To-School Spectacular at the 10,000-seat Sam Houston Memorial Coliseum. The lineup included Johnny Winter, Ray Stevens, Jerry Lee Lewis and The Everly Brothers (the following year, the Beatles would headline).

It was to be David Box’s final performance.

David and Ray Rush planned to fly on Saturday, October 24, 1964 to Nashville, where the contract for David Box’s first RCA Victor LP was waiting to be signed. The day before, David, Buddy Groves and Kings bass player Carl Banks decided to take a quick flight to Houston in a rented Cessna 172 Skyhawk.

Buddy Groves’ pal Bill Daniels was a qualified pilot. As they all climbed in and crammed into the single-engine four-seater, maybe the guys joked, as many musicians have, about Buddy Holly’s fateful flight. There were four of them, just as there were in that Beechcraft Bonanza. At least they’d be safe. Coincidences like that don’t happen. Not twice. Not with two guys who sang with The Crickets.

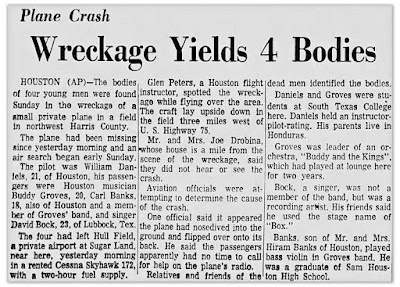

They took off from Hull Field, a private airport in Sugar Land. The Cessna supposedly had enough fuel for a two-hour flight. About fifteen minutes in, the plane disappeared.

Glen Peters, a flight instructor from Houston, spotted the wreckage that Saturday morning. The aircraft lay upside down in a field in north Houston, about three miles west of Highway 75. The plane had apparently nosedived into the ground and flipped on impact. There were no survivors. Investigators would blame a defective fuel gauge.

“It was a pleasure flight,” Rita said. “He and some of his musician friends from Houston decided they wanted to go up and it just did not end the way it should have. And so fate stepped in. Death takes a plane ride and David, he’s gone.”

Rita was sixteen. “Right,” she said. “And I’m really not going to go there.”

She did agree to go back in time to that weekend, in the family home, after the crash was confirmed, and tell us the truth about a story that sounds too much like legend: that the first people to visit the Boxes were Buddy Holly’s parents, and that L.O. Holley said to Mr. Box: “People would tell you that time heals the pain, but it does not.”

“Yes, that is very true,” Rita confirmed. “There was also an Avalanche-Journal newspaper reporter. That’s our local newspaper. The AJ reporter was in the house. He was the first to arrive. And then there was knock on the door and it was Mr. and Mrs. Holley. They were the first visitors. And so there is a quote in the AJ newspaper of what Mr. Holley said to my dad. I was standing right there when Mr. Holley walked in the door and embraced my dad and told him, ‘You know, people would tell you that time heals the pain, but it does not.’ And Mr. and Mrs. Holley stayed the evening and it was amazing.”

And was what he said true? Does time not heal the pain?

“No,” Rita Box Peek said, fifty-four years after the fact. “It does not. It does not.”

SINGING THROUGH ETERNITY

“It’s very important that people understand that David was not a wannabe. That has been something that naturally is going to come back from time to time, from people who don’t know anything. And the first thing that comes to their mind: ‘Well, he sounds like Buddy Holly, well he sounds like Roy Orbison, well, he must be a copycat!’ Well, he is not!” Rita laughed at that notion.

David Box released four singles, eight songs in his brief career. From a cursory listen, one could write him off as a talented also-ran. It wasn’t until the fiftieth anniversary of his death, and the release of two “David Box Story” CD sets, that his talent and promise were made clear. The ninety-four recordings include just about David Box’s entire recorded output, and the compositions, arrangements and vocals recorded at Ben Hall’s Big Springs studios clearly show an artist pushing beyond the template left by Buddy Holly. In fact, the epiphanies among the run-throughs of some Holly songs aren’t that different than those found in similar early takes from the Beatles Anthology albums.

While others have profited from the collections, Rita Box Peek remains the keeper of David Box’s flame. She’s donated much of his material to the archives of Texas Tech University, arranged a fiftieth anniversary tribute at Lubbock’s Buddy Holly Center, and in 2014 helped produce a tribute album, “Out of The Box,” in which Lubbock musician Brian McRae performed solo jazz-inflected guitar versions of David Box originals (played on David Box’s Strat).

“I wanted to get David out of the Sixties, because he’s already played those songs his way.” Rita explained. “And knowing David, he would have gone beyond just the same notes over and over. He would have gone into what Brian did, where he extended the songs and translated them into different melodies. Each of those melodies had far more potential than what 1960 would allow an artist to do, or a listener to appreciate.

“That was my inspiration, doing this David’s way, how I really know and believe that he would have done something like this. He would’ve wanted it this way.”

This month, “Out of The Box” is finally available through the CDBaby website. So is an album called “Just for You,” Rita Box Peek’s first jazz album. The sublime collection was produced by McRae, more than fifty years after David’s death led Rita to give up her musical ambitions.

David Box would be seventy-five now, an age at which many of his contemporaries are still going strong, still creating.

“When David got killed, it had an effect on a lot of people,” BJ Thomas said. “The sadness of it, and the fact that he wouldn’t be able to present his music and we’d never see what he could have done.”

Glen Spreen, a member of Buddy Groves & The Kings who went on to arrange and produce for artists ranging from Elvis to Johnny Mathis, spoke of David Box shortly before his own death in 2016: “He was a disciplined and sensitive musician, confident and decisive while performing, whether it was live or recorded. I have worked with a very small number of singers who have impressed me as much as David.”

“I’ve thought about him a lot over the years, how short his life was, but how ambitious and focused he was on being a musician,” Terry Allen told us. “I had a friend who died young and at his funeral, his mother said, ‘Yes, he didn’t live very long… but he stayed up late.’ That’s how I think of David and a lot of those artists cut down too early. He made a lot of music in that little slot of time fate gave him. He made the time matter. He stayed up late.”

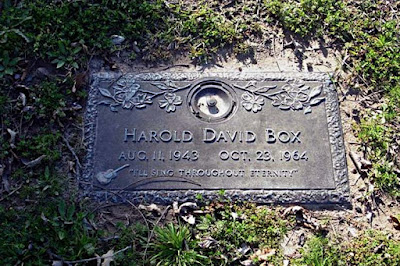

David Box is buried at Restlawn Cemetery in the city in which he was born. His grave marker reads “I’ll sing through eternity” — and he will, if his kid sister Rita has any say. “David was a comet on fire on the edge of something great,” she said. “It’s true there will be a select few individuals in this world whose lives will deeply affect each one of us in mind, body, and spirit. My brother David is that kind of soul.”

/div></div>

###

BURT KEARNS & JEFF ABRAHAM have written a book about performers who died on stage. THE SHOW WON’T GO ON will be published in 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment