SHA NA NA & THE ESCAPED BABY-KILLER

October 9, 2018

How guitarist ‘Vinnie Taylor’ came back to life 20 years after dying of a heroin overdose and fooled the cops for four years while allegedly playing in the retro rock & roll band that Jimi Hendrix brought with him to Woodstock

by Burt Kearns & Jeff Abraham

Dozens of musicians have performed as members of Sha Na Na during the group’s 49 years as America’s premier rock ‘n’ roll parody show band. Among the ones who’ve come and gone, few were as steeped in the grease-dripping, golden oldies era, or committed so intensely to his character, as Chris Donald.

Taking the stage name “Vinnie Taylor,” the lead guitarist came onboard in time to play on Sha Na Na’s first and most significant albums and to lead the band in its touring heyday, until 1974, when he was found cold and blue in a motel room, with a needle hanging out of his arm. Chris Donald, aka Vinnie Taylor, was dead — dead, that is, until he came back to life and began performing again twenty years later.

The story of the death and resurrection of Vinnie Taylor is one of the most confounding, bizarre, unwelcome and sordid stories in the history of rock ‘n’ roll.

But first, you’ve got to know the story of Sha Na Na.

And Na Na Sha.

IN THE CONTEXT OF CHAOS

Sha Na Na, the group that led the rock ‘n’ roll revival of the early Seventies, was born not on the streets of Philly or under a boardwalk in Coney Island during the Eisenhower era, but in 1969 on the rarified campus of Columbia University, the Ivy League school in upper Manhattan. “The original band were glee clubbers,” recalled Scott Simon — “Screamin’ Scott Simon” to you, Sha Na Na’s legendary piano man. “They were a Columbia group called The Kingsmen — not to be confused with the ‘Louie, Louie’ Kingsmen, which caused them to change their name early on in their professional career to Sha Na Na. These guys were short-haired, wore blazers and didn’t have any electric instruments. They had acoustic guitars.

“It was happening in the context of the chaos on the Columbia campus and what might bring together the two groups known as the jocks and the pukes,” Simon said. “Pukes being the hippie peace lovers, and the jocks being the hard-drinking football players. Who also would take acid on the side, by the way.”

The group’s mission came into focus when “they added the electric players: Jocko (Marcellino) the drummer, Bruno (Clarke) the bass player, and Henry Gross the guitar player.”

Their show, full of dancing, posing and flexing — along with some proto-punk rock ‘n’ roll — wound up playing The Scene, Steve Paul’s happening basement nightclub on West 46th Street in the Theatre District. The Scene was where it was at music-wise, booking acts like The Doors, The Velvet Underground and The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Hendrix took a liking to Sha Na Na, and gets some credit for “discovering” the group. When he was booked to perform at the Woodstock festival that summer, he insisted Sha Na Na be his opening act. It was their eighth gig.

“Hendrix wouldn’t go on until Sha Na Na went on,” Simon said. “So six in the morning, Monday morning, Sha Na Na went on. And 7:30 in the morning, Jimi went on. The very last things at the festival.”

While Sha Na Na was about to break nationally that Woodstock weekend, Scott Simon was on West 3rd Street in Greenwich Village, playing the Café Bizarre (“home to the Lovin’ Spoonful and all these Village-y acts”) with The Royal Pythons, a four-piece blues and rock ‘n’ roll band led by his Columbia classmate, guitarist Chris Donald. His time in Sha Na Na was months away.

“I got into Sha Na Na because the piano player left,” he said. “I was the first guy not from the original twelve guys. April of 1970, I joined the band, graduated in May. So got a job. Get a job. Sha na na.” Simon laughed at that (Sha Na Na took their name from the nonsense syllables in “Get A Job”, the 1957 doo-wop hit by The Silhouettes).

Chris Donald got the call ten months after Screamin’ Scott. “He joined in ’71, and was in the band for three or four years. He played on all of our seminal albums,” Simon said. “And he adopted the stage name Vinnie Taylor, so he was Vinnie. And he was the greasiest guy, really. If you look at those photos, with a toothpick and a striped shirt and sunglasses, he was not pretending. He was for real.

“He had gone to private school in Kent, Connecticut. His father was in the State Department, in the CIA. His parents were very nice people, but they were traveling internationally, so they’d send their kids to boarding school and these very straight, strict environments. And very often, the bounce-back was severe. So Chris came to Columbia with the longest hair, did the most drugs and was notorious for that in an era at Columbia, from ’66 to ’67, to ’68 to ’69, as the revolutions came one after the other. He was definitely caught up in the cultural stuff. But he also had an unfortunate predisposition to want to get really high.”

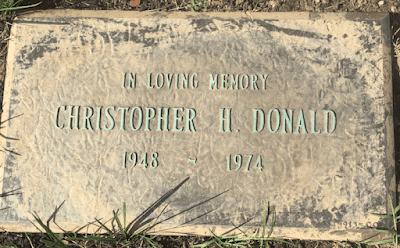

On Friday, April 19, 1974, Sha Na Na performed at The University of Virginia’s University Hall in Charlottesville, a stop on tour promoting their album, Hot Sox. After the show, somebody found Vinnie Taylor in his motel room, dead from a heroin overdose at age 25. The next night’s sold-out show in Pittsburgh (4,000 tickets had been sold) was canceled.

“Well, it was not unexpected to some extent,” Simon admitted. “I think anybody that has had a friend that has been dabbling in hard drugs knows there’s a possibility that the day will come. And the story where you get a batch that’s too pure, not cut enough and that’s too much — I think it’s a very common problem. Much too young. Much too young.”

They buried Vinnie Taylor in Falls Church, Virginia. Sha Na Na replaced him with Elliot Randall (famed for his guitar work on Steely Dan’s “Reelin’ In The Years”). Randall stayed with the group for about a year. Other members stepped in and moved on as Sha Na Na became an act for all ages with a syndicated television variety series and an appearance in the movie Grease (and one of the best-selling soundtrack albums of all time). Sha Na Na became mainstream.

And with that, came the imitators.

NA NA SHA

“There was a band out of Louisiana that was kind of a bar band, a show band that called themselves Na Na Sha. Yeah. ‘Na Na Sha.'” Even over the phone, you can hear Scott Simon shake his head. “And that was in the early days of Google, where if you hired somebody and sat there and typed in your name ten thousand times, you’d rise up in the Google listings. So it got to like, when you’d look up Sha Na Na, ‘Na Na Sha’ would come up number three.”

Simon got wind of the group with the disturbingly similar name some time in the 1990s, but Na Na Sha had been performing as an unauthorized Sha Na Na imitation since 1974. While the originals began as college choristers, Na Na Sha were members of a church choir in the town of Gonzales, Louisiana. Na Na Sha’s stage act was a copy, with parodies of Fifties artists from Elvis to Fats Domino, some skits and even a skinny, flexing Bowzer lookalike.

“Now what do you do with that?” Simon asked. A cease and desist letter? A lawsuit? Too much trouble. Imitators, rip-offs and “tributes” are products of success. “But tribute bands are one thing. Portraying yourself as a member of the band is another. And there are constantly people showing up, emailing, texting or sending stuff to our website saying, ‘Do you remember so-and-so? He was with your band?’ And, “No, I don’t remember. It’s nonexistent!’ Lot of claimants. But about fifty people have performed under the banner of Sha Na Na in fifty years.”

By the time Na Na Sha had surfaced, Scott Simon and the group figured they’d heard it all. Until they got word that Vinnie Taylor was back, that he’d risen from the dead and was headlining gigs in Florida.

SNN 1

He showed up in St. Petersburg on the Gulf Coast in a black customized conversion van with the license plate “SNN 1.” He was twenty years older than when he’d supposedly left this mortal coil. He still had the pompadour, but it was silvery and coiffed with hair spray instead of grease. He wore a gold satin Sha Na Na jacket. He had a gold Sha Na Na necklace. He had the shades and he had a guitar and he could really sing.

Vinnie Taylor even had a website that announced “The Bad Boy is back!”, and if anyone doubted what he claimed, he’d pull out Chris Donald’s birth and baptism certificates and a Social Security card. When someone mentioned to Vinnie Taylor that he was supposed to be dead, he explained that he’d faked his death, and spent all these years working undercover for the CIA — coincidentally, just like his dad did. That was why he had a new name, Danny Catalano — “Danny C.” to his fans.

Danny C. was Danny Catalano and Danny Catalano was Vinnie Taylor, and Vinnie Taylor was Chris Donald — and Scott Simon knew that Chris Donald was dead. He was his pal. He’d seen the corpse. So when somebody gave him a call to say there was a guy selling out clubs and performing in bars and at car shows in Florida, claiming to be Vinnie Taylor, Scott Simon wanted to scream. This guy was full of it! A fraud!

Then again, “What do you do with that?”

“It was brought to our attention at some point, but it was nothing, you know?” Scott Simon reasoned. “He was just playing small clubs in Florida. I think we sent him a cease and desist letter.”

Anything else would just give the mook more publicity.

Meanwhile, Vinnie Taylor-Danny C. was getting regular gigs and developing a real fan base. He’d found a girlfriend named Jessica. They moved in together, in an apartment right on the water. Jessica believed his tales of Sha Na Na and the CIA, and was forgiving when he acted a little funny sometimes.

“We would be in bed at night and he would just jump out of bed and run to the window,” she said. “He never wanted people coming into our apartment, and he would tell me a lot of times, ‘Whatever you do, just don’t bring up the Sha Na Na thing’.”

Danny C. had a reason to be paranoid. And his years in the CIA had nothing to do with it.

BABY KILLER

Vinnie Taylor AKA Danny C. was actually Elmer Solly — make that Elmer Edward Solly, because this kind of guy, from Lee Harvey Oswald to John Wayne Gacy, always gets all three names when you write about him.

In 1969, the year Sha Na Na was formed, Solly was living in Camden County, New Jersey. He was a bad guy back then, and an even worse drunk. Those two sides came together on the evening of July 25, 1969, three weeks before Woodstock, when, in a drunken rage, he beat his girlfriend’s son to death. Solly was twenty-three. His victim, Christopher Welsh, was a two-year-old baby.

Solly turned himself in two days later. He blamed the booze and claimed the killing was an accident. He went on trial, and on April 16, 1970, around the time Scott Simon was graduating from Columbia and joining Sha Na Na, was convicted of manslaughter. He was sentenced to 15 to 20 years and shipped off to the maximum security Trenton State Prison.

Corrections officer Mike Green, left, escorts convicted murderer Edward Solly from a van at Jersey State Prison in Trenton, N.J. Friday, May 18, 2001. Solly escaped in 1974 while on furlough from a New Jersey prison where he was serving time for murdering his girlfriend’s 2-year-old son. Solly spent spent 27 years on the lam and posed as a doo-wop singer. (AP/N.J. Department of Corrections)

Solly had someone in his corner, though, someone who knew how to play the system. His mother, Edna Bolt, got right to work on a letter-writing campaign, claiming her son was being mistreated by guards. Her work, with help from Solly’s grandmother, got him transferred to a medium-security prison in Cumberland County in 1974.

Edna wasn’t finished. She began another letter-writing campaign, this time to get her boy a furlough, a day pass to visit some sick relative. By June, Solly was making his third visit home. He was accompanied by a psychologist instead of a prison guard. When the head-shrinker allowed him to make a detour and hook up with his girlfriend in a motel, he went in the front door and slipped out the back. Elmer Edward Solly was in the wind.

He didn’t go far — not at first. A year after he escaped, Solly was arrested in Philadelphia for receiving stolen goods. Master criminal that he was, he gave the cops a fake name. They turned him loose.

The law had another shot at Solly in 1979 when a cop pulled him over for a traffic violation in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Again, he offered a fake name and was sent on his way.

This time he went off the radar completely.

Police leaned heavily on Solly’s mother, but she kept mum. The rest of the family stayed in line. As long as Edna was alive, they wouldn’t give the cops the time of day.

With no other leads, the state trooper in charge of the case looked at the bright side. “Our whole belief was that he would be underground, he’d be holed up in a homeless shelter somewhere and we’d never find him,” Detective Louis Kinkle said. Kinkle figured “he’d die in the woods somewhere and we’d never find him.”

Elmer Edward Solly stayed off the radar for 20 years. He remained underground until 1997, when he showed up in Florida, online, on video, in concert, in person… in plain sight.

GONE FISHIN’

“Florida is a place for misfits and losers,” Marvelous Marvin Boone, an oldies radio jock in St. Pete explained to a reporter. “You come down here, you can be Elvis’ bodyguard for a year.”

The Sunshine State is also a place where someone can take on the identity of an obscure musician from a well-known musical group and cash in on the scam. Only most of the time, he’s not a convicted baby killer or escaped convict, let alone both.

Detective Kinkle re-opened the cold case in 1999. It didn’t get any warmer until Edna Bolt died the following March. As soon as her body was cold, her widower Harry told the cops that Elmer Edward Solly was down in Florida, calling himself Danny C. The cops were more than a little surprised to find Danny C. flaunting Solly’s mug and tattoos on his website.

At 10 p.m. on May 10, 2001, six U.S. Marshals converged on Danny C.’s home at the Sand Cove Apartments. They found him on a small dock out back, fishing in the inlet. Right nearby was his van, emblazoned with his website address: www.shananadannyc.com.

When they grabbed him, Danny C. denied being the guy from Sha Na Na. He denied being Elmer Edward Solly. He could not deny his fingerprints.

When the news spread, folks in Florida admitted they had suspicions about the guy — but boy, could he sing! “I got to be honest. The guy came in, he did a good show. We had no idea,” said oldies promoter Scott Robbins. “The whole thing is insane. This is not the way Richard Kimball (from The Fugitive) conducted himself. What kind of idiot puts up a website?!”

Headshot of fugitive Elmer Edward Solly. Solly was captured in Florida. 5/18/2001

After 27 years on the lam, Elmer Edward Solly was returned to the state prison in Trenton on May 17, 2001. He was crying and apologizing when he stepped out of the police van. He was 55 years old. He was sent to the medium-security Riverfront State Prison to serve out his sentence, with some more years tacked on for escaping. When he was paroled in 2003, he did not resume his oldies career.

He wound up living in a welfare motel and died in 2007.

“Why he decided to make himself so visible, only the Lord knows,” said Screamin’ Scott Simon.

FIFTY YEARS

“It’s really not something you want to trade on or talk about too much,” Simon said of the episode. “One of the principles of PR before the new media used to be, ‘Did they spell your name right?’ And so any mention is a good mention. But you don’t want to stay in the news because a guy who killed this two-year-old child is using your name and likeness to have a performing career. It’s disgusting. But things happen, and you know, we’re generally speaking a pretty anonymous bunch of guys. It’s not like, ‘Wayne Newton– was he in the Mafia?‘”

File Elmer Edward Solly along with Na Na Sha. Remember Na Na Sha? Well, the cease and desist letter didn’t have much of an effect. They’re still out there, and booked well into 2019, the year the group will mark forty-five years imitating the real thing.

The real Sha Na Na, featuring Screamin’ Scott Simon, original members Donny York and Jocko Marcellino and four sidemen, still performs ten to twenty dates a year. The group celebrates its fiftieth anniversary (and fiftieth anniversary of its Woodstock appearance) in 2019.

“We’re trying to design a show that’s similar to a lot of other shows, where you tell the history and there’s music that illustrates the story,” Simon revealed. “It goes back to when we were a glee club, before the band got together, and shows the evolution of the whole thing through the Woodstock movie, the Grease movie, the TV show and all the years beyond.”

It also offers a chance to shine a spotlight on the real Vinnie Taylor.

“Vinnie was a good friend of mine,” Simon said. “And he was a real great player. His idol was probably Keith Richards, and he could play just about anything, could finger-pick and rock as hard as anybody. But sadly, he had his own demons, as so many people did, and left us.”

Scott Simon

###

BURT KEARNS & JEFF ABRAHAM have written a book about performers who died on stage. It will be published in 2019.

No comments:

Post a Comment